1959

Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn

Case study by:

Dalton Roberts,Fri Oct 09 2015

Fox Building

Introduction

The Fox Building, designed in 1959 by New Mexico-based architectural firm Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn, stands on the southeast corner of Madeira Drive NE and Domingo Road NE in Albuquerque. An architectural remnant of the city’s foray into the modernist aesthetic, the Fox Building represents an amalgamation of European modern architectural ideals adapted to the harsh New Mexican high desert climate. The building in its original form appeared as a minimal, translucent rectangular mass bookended by two thin, black brick facings.

Design and Construction

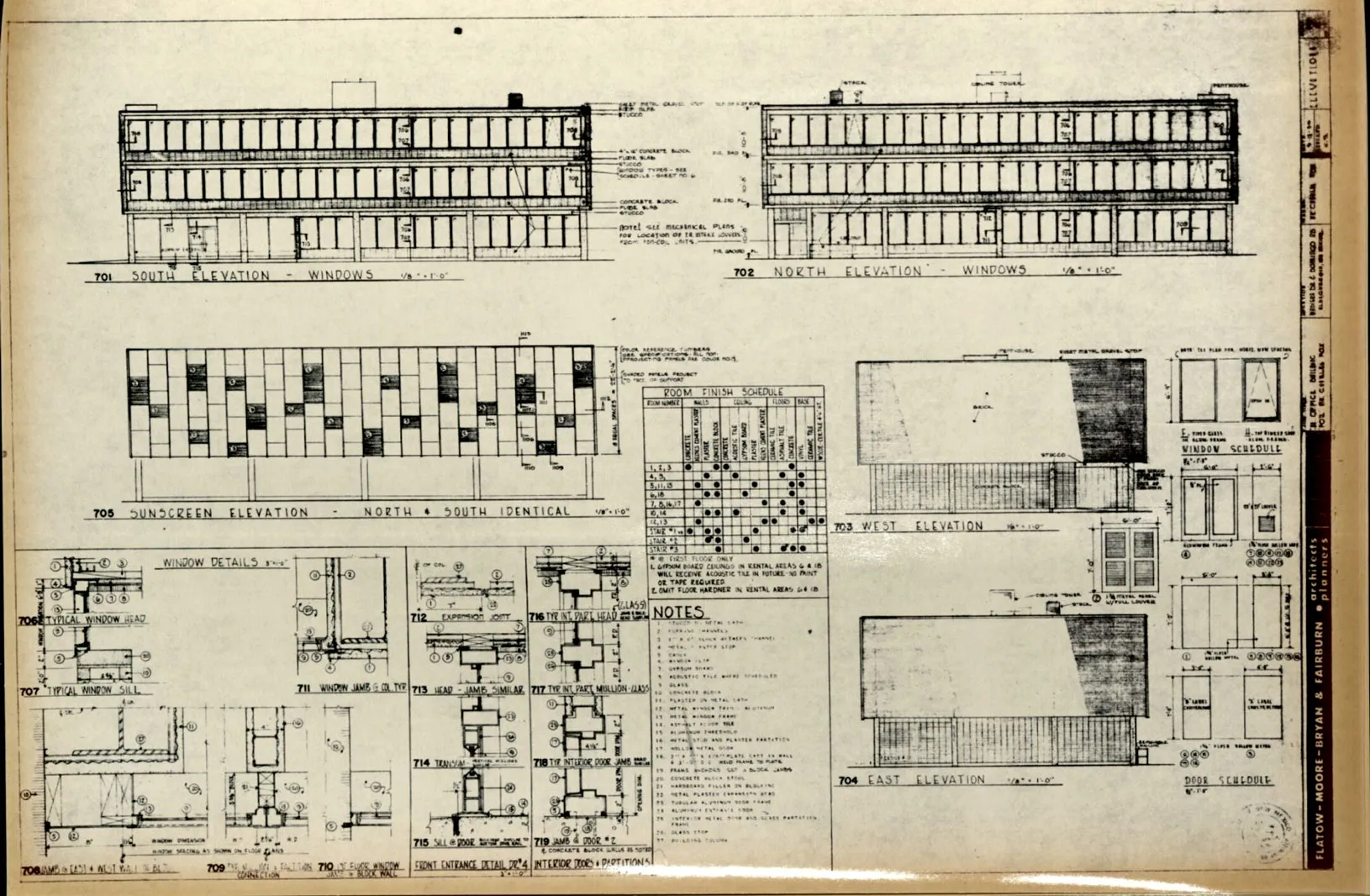

The translucent effect that distinguished the Fox Building was created by a metal screen system, specified in the building’s original construction documents as “sunscreens.”1 The sunscreens concealed the second and third floor’s curtain wall facades on the northern and southern elevations. A narrow catwalk, approximately two feet in width, separated the sunscreens from the adjacent curtain walls. The catwalk’s width was sufficient to create a vague outline of the curtain wall and other structural elements when viewed through the sunscreen. The effect, a translucent rectangular mass, sat upon a slightly smaller base comprised of northern- and southern-facing storefront windows and concrete block end-walls covered with a rough, natural rock and mortar veneer. Even today, the unassuming structure exhibits a quiet dignity that characterized much of the work that Flatow’s firm produced in the middle of the twentieth century, an era of great change in Albuquerque.

In the early 1950s, the city of Albuquerque began aggressively annexing land on its East Mesa in response to the large influx of soldiers returning from World War II who were attracted to the region by job opportunities at national weapons laboratories and other federal offices.2 The consequent outward growth in effect stymied commerce in the downtown area by causing a flourishing of development in the eastern sections of the city, where private developers anticipated the need for office and retail space to serve, and benefit from, this rapidly growing population.3 The city itself played no small part in this, adopting a more nodal approach to development that included an effort to establish a new commercial hub on Central Avenue east of Carlisle Boulevard. New buildings that rose in this growing area as a result included Highland High School, Hiland Theater, White’s Department Store, J.C. Penney, and many others.

The Fox Building was among the new structures to rise on what was then the city’s eastern edge. According to its current owner, Rom Barnes, developer Charles Fox purchased and constructed the three-story building as an anchor project for the area. Fox’s intended purpose was to create leasable commercial office space. In the booming city he had little trouble finding interest, soon attracting the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company as its first tenant.4 This success in turn attracted other projects to the area, most notably the modernist, seventeen-story First National Bank Building East. Constructed adjacent to the Fox Building at the major intersection of Central Avenue and San Mateo Boulevard, it too was designed by Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn and completed just four years after its smaller predecessor, in 1963. In an ironic twist, however, the height of the bank building caused wind turbulence that ultimately damaged the southern sunscreen façade of the Fox Building, leading to the removal – from this side of the building – of the functional and decorative elements that gave the building its unique character.5

Influence and Style

Flatow’s work at the Fox Building and in his other projects drew heavily from that of International Style architects like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Likewise, it similarly expressed the progressive, technology-oriented, and idealistic collective mind of the era. Flatow established his firm in 1947 with former college roommate Jason Moore. Being a firm believer in innovative architectural design, Flatow’s work, like most modern architecture, was self-referential and did not explicitly acknowledge the culturally based formal vernacular of New Mexico. The firm’s design repertoire, which consisted primarily of commercial architecture, was likely meant to appeal to the great influx of families who took root in Albuquerque in the postwar period, most of whom had no cultural connection to the Southwest. As a result, Flatow’s strategy largely drew connections to national and global trends, rather than local traditions.

The Fox Building demonstrates features of this modernist aesthetic, with its rectilinear geometry, flat roof, simple façade, glass curtain walls, and exposed structural elements, such as columns and floor plates. The building’s layout featured an open floor plan that was meant to accommodate a variety of tenant needs by the use of removable partition walls. The design of the lighting, heating and cooling, and communication systems lent themselves to this concept of modularity. Both aspects – the open plan and an emphasis on modularity – were characteristic approaches of modernism. These elements also responded to the broader shifts in the American workforce at this time, from agricultural and industrial manual labor to white-collar jobs, which brought a new prominence of the office as a workplace. Modernism sought literally and figuratively to express the technological advancements that both gave rise to and resulted from this age. As at the Fox Building, this took the form of new, highly engineered construction materials and advancements in heating and cooling systems, with radical design the result.

At the time of the Fox Building’s conception, air conditioning was becoming increasingly common throughout the Sunbelt states, making expansive glass possible in a region where vernacular architecture typically made use of massive earthen walls to resist the harsh desert environment. Although the project included a rooftop cooling tower and chiller, and the architects did employ glass amply, Flatow’s firm nonetheless made a conscious effort to address these climatic conditions by the use of a double-skinned screen system on the northern and southern facades. Not only did the building’s sunscreens mediate environmental conditions, they also concealed the exterior components of the upper floors, melding them into a cohesive unit that extended approximately two feet beyond the basic structure, creating the illusion of a floating mass. Inside, the Fox Building also made use of a wide array of modern manufactured materials and fixtures. These included aluminum handrails and mullions, wood paneling, linear florescent strip lights, Celotex ceiling tiles, and asphalt floor tiles. Heat arrived by way of wall-mounted radiant heaters supplied by a boiler located in the basement.

Modernism and the Cold War

Despite the international discourse that the Fox Building tapped into architecturally, there are nonetheless traces here of the region in which Flatow made his career. At the very least, these features represented efforts to humanize the modernist language, a characteristic that Flatow maintained across his projects. The western façade includes rock facing on the ground level, with vertical breaks in the stone that expose the repetitious concrete columns that support the structure. Initial elevation plans do not show a stone façade here, so perhaps its addition was an attempt to relate to the natural Southwestern landscape and to add interest to an otherwise solid wall.6 Black brick façades cap the eastern and western ends of the upper stories, adding to the continuity of the floating mass but also introducing the smaller unit of the brick. The lack of west facing windows was likely an attempt to resist the blinding afternoon sunlight and heat, an acknowledgement of the region’s climate. Similarly, the entrance into the building, an off-center recess in the southern ground floor façade, is reminiscent of the zaguans of early Spanish Colonial architecture in New Mexico and directs movement from the parking lot into the lobby. Yet one is quickly drawn out of any historical images such design moves evoke. Above the lobby door, a sign is posted indicating the presence of a fallout shelter beneath the Fox Building, a bleak reminder of the anxious and uneasy feelings of Americans during the Cold War era in which this structure took form.

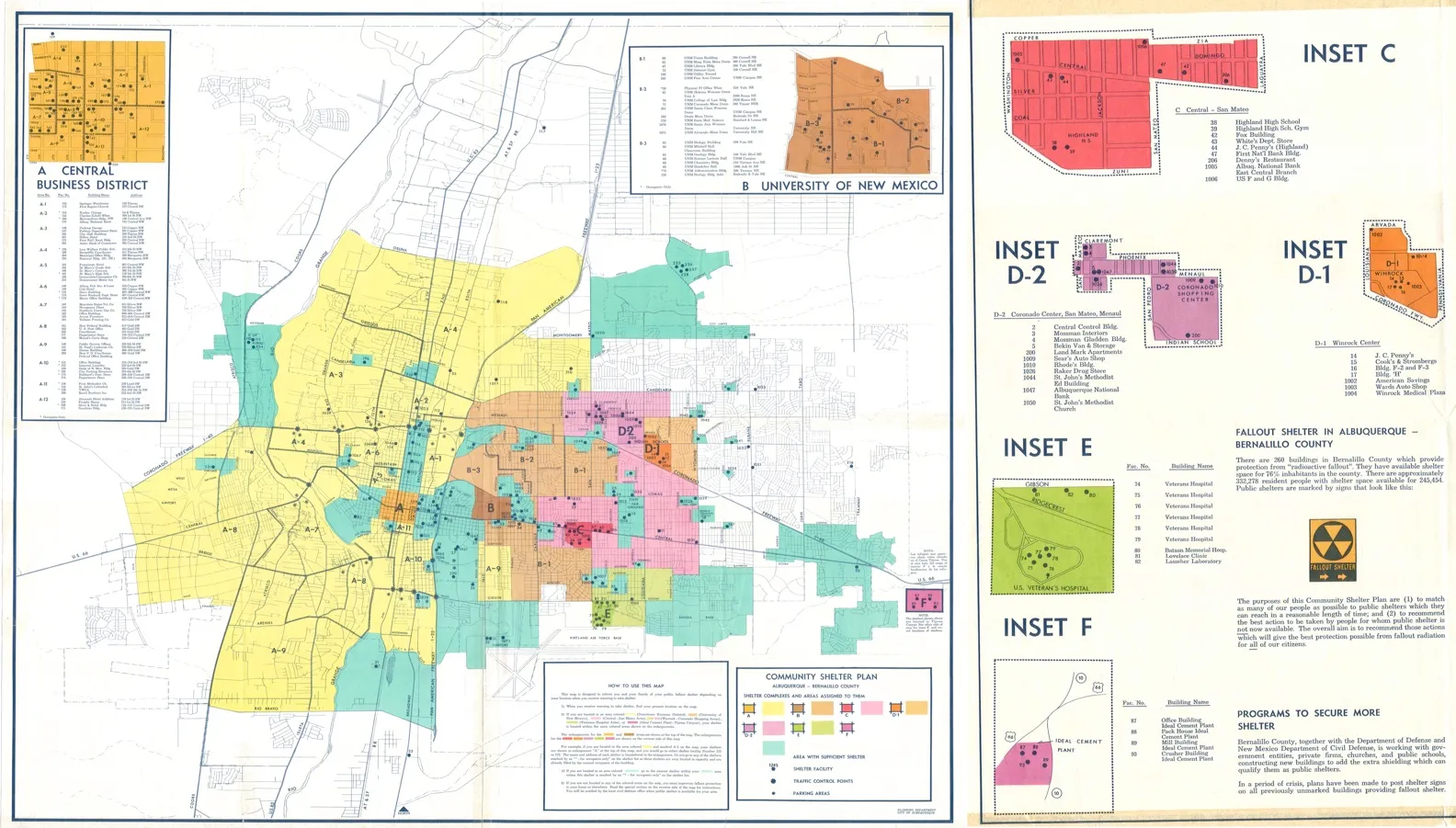

For New Mexicans, of course, the Cold War was more than a distant reality; it was a very local one. New Mexico played a primary role in the development of the atomic bomb during World War II. The first A-bomb was designed at Los Alamos Laboratory under the direction of physicist Robert Oppenheimer, a covert endeavor known as the Manhattan Project. The Trinity Test, the first test of an atomic bomb, occurred at what is now the White Sands Missile Range, near Alamogordo, in 1945. In 1948, Sandia National Laboratories opened in Albuquerque to further test and develop atomic weaponry, making the city a prime target for nuclear attack during the Cold War. As a result, many new buildings were built and designated as fallout shelters, a chapter of mid-century modernism that the Fox Building also relates to. Albuquerque’s Planning Department developed a plan in coordination with the Albuquerque-Bernalillo County Civil Defense Agency that strategically located community fallout shelters throughout the city.7 The Fox Building was one of nine buildings containing fallout shelters in the Central-San Mateo area, intended to accommodate citizens within a defined zone as prescribed by the Community Shelter Plan in the event of a nuclear attack.8

These fallout shelters became part of regular life for residents of Albuquerque. According to a recent article, “One Tuesday a month, at noon, a shrill alarm would ring out across Albuquerque. This was during the Cold War,” says Herman Bishop, who was the Albuquerque Fire Department liaison to the Office of Emergency Preparedness, which was part of the Civil Defense Program at the time. The sound heard throughout the city wasn’t a drill. ‘It was a reminder,’ Bishop says. ‘At that time, the possibility of an attack was very real.’”9 According to the Community Shelter Plan, the Fox Building was able to accommodate 127 people in its basement.10 When the current owner purchased the building in the 1980s, some shelter provisions still remained in this underground space.11

This was a bleak reality with which Flatow had intimate familiarity. Following his receipt of an architectural engineering degree from the University of Texas-Austin in 1941, he became a first lieutenant in the army, working initially for the Army Corps of Engineers building air bases and other military facilities. In 1945, he moved to New Mexico as a member of the Manhattan Project, in order to design buildings for research on the atomic bomb. He met with project leader Robert Oppenheimer during his involvement. Flatow himself would certainly have been well aware of the effects of nuclear fallout. Living in a state that was instrumental in the development of the atomic bomb influenced the direction of his architectural career. It also made it possible for him to achieve great success in a booming region fueled by the Cold War.12

Conclusion

This modest building embodies all of the simultaneous optimism and horror that attended the postwar age. Buildings like this one embraced the new technological possibilities of their era. Indeed, these modernist technological innovations were perceived by the public as bringing security in the event of nuclear attack. Yet the very evils enabled by this same modern technology resulted in the need for this protection. In reality, the concept of the community shelter plan and the implied meaning of modernism itself were both flawed. Technology came with tremendous benefits, to be sure, but also unimaginable costs. Concrete shelters could not prevent total annihilation. Such measures gave people a false sense of security in the postwar era.

Modern structures such as the Fox Building capture this crucial moment in history, yet they are currently in an uncertain state: on one hand, considered classics worthy of preservation; on the other, targeted as the next victims of the wrecking ball. Many Victorian buildings were torn down and viewed as eyesores in the mid-twentieth century, but now the remnants of that era are in demand as historical landmarks, suggesting the danger of rendering final judgment on the recent past. The Fox Building and many other small but carefully designed modern structures comprise an important segment of Albuquerque’s architectural heritage and remain functional and viable parts of its urban landscape. Their persistence, fallout shelters and all, is essential to a full telling of the city’s complex postwar history.

Footnotes

-

Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn, Elevation Drawings, Office Building for Mr. Charles Fox, 1959, Box 1 (unfoldered), Flatow, Moore, Bryan, & Fairburn Job Files (MSS 801 BC), Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM. ↩

-

David Kammer, “Post-War Suburban Expansion 1945-1959,” New Mexico History.org, August 2000, accessed 29 November 2015, http://newmexicohistory.org/places/albuquerque-1945-1959. ↩

-

Robert B. Fairbanks, “The Failure of Urban Renewal in the Southwest: From City Needs to Individual Rights,” Western Historical Quarterly 37, no. 3 (Autumn 2006): 303–25. ↩

-

Rom H. Barnes, interview by author, Albuquerque, NM, 1 December 2015. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn, Elevation Drawings, Office Building for Mr. Charles Fox. ↩

-

City of Albuquerque Planning Department, Community Shelter Plan, Albuquerque-Bernalillo County, New Mexico: Final Report (Albuquerque: City of Albuquerque Planning Department, 1968). ↩

-

City of Albuquerque Planning Department, Community Shelter Plan, Albuquerque-Bernalillo County, New Mexico (Albuquerque: Albuquerque-Bernalillo County Civil Defense Agency, 1968). ↩

-

“Fallout Shelters from the Past,” Albuquerque the Magazine, 1 December 2013, 58-59. ↩

-

Community Shelter Plan, Albuquerque-Bernalillo County, New Mexico: Final Report. ↩

-

Barnes, interview. ↩

-

“Inventory of the Flatow, Moore, Bryan & Fairburn Job Files, 1957-1984,” Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico, accessed 29 November 2015, http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmumss801bc.xml#idm212832. ↩