1960s-1970s

City of Albuquerque Planning Department, with Various Architects and Planners

Case study by:

Max Boruff,Fri Oct 09 2015

Downtown Urban Redevelopment

A Changing Vision: Albuquerque’s Urban Renewal

In many ways Albuquerque has always been a city governed by the transportation routes carved through it. From the early trails of indigenous peoples and Spanish explorers to the American railroads and highway system, Albuquerque bears the marks of history in its roads. As different modes of transportation changed the way people interacted with the city, however, they began leaving a very different mark on Albuquerque’s urban vista.

In contrast with the railroad boomtown of 1880, the Albuquerque of the early 1950s was a strikingly different place. Paved roads, sprawling suburbs, and a city grid which no longer wound its way around natural obstacles but instead plowed through them decidedly dated Albuquerque as a twentieth century city. In the immediate postwar period, downtown still held its own as the center of everything that mattered to residents. From shopping to social engagements to government, the facets of daily life had prominent seats here. Department stores such as Sears and Montgomery Ward shared streetscapes with both small shops and grand buildings like the Hotel Franciscan. The dense neighborhoods surrounding the urban core were bustling and community driven, with a thriving sense of identity.

1956 Federal Highway Act

Then came the Interstate, launched officially with the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, followed in short order by the first regional class shopping center in the state, Winrock Center, completed in 1961. Subdivisions began sprouting like weeds on the city’s East Mesa, helmed by merchant builders such as Ed Snow and Dale Bellemah. With the city growing in population and area, soon downtown wasn’t as bustling as it had been in its Route 66 heyday.

This was a story confronting many cities across the United States during the postwar period, as a so-called “urban flight” developed, a rapid migration of population and commerce from urban centers for greener pastures. First went the residents, who flocked to the newly built suburbs in droves, eager to leave behind crowded urban neighborhoods and apartment houses for their own piece of the American dream. Businesses quickly followed, uprooting themselves from prominent positions downtown to suburban shopping malls and strip centers.

Albuquerque was no different, even if its growth came later than coastal cities and the urban flight from its downtown core occurred at a somewhat slower rate. By the beginning of the 1960s, the heart of Albuquerque’s downtown, called the central business district or CBD by many contemporary studies, was looking less like a thriving urban center and more like a sleepy ghost town. This is not to say there was not still activity in the CBD, nor that every single business had fled for a storefront along Winrock’s airy mall corridor. The majority of rentable square footage was still occupied by the time serious discussions about federally backed urban renewal began to circulate amongst city officials in the 1960s, yet those officials understood that the city’s commercial balance had begun to shift markedly away from the city center.1

Urban Renewal

Albuquerque was one of the later cities to look at adopting any form of urban renewal, a practice established by the Federal Housing Act of 1949 though not named as such until passage of the Housing Act of 1954. These acts provided for the large-scale improvement of urban areas riddled with “blight,” a catchall term used to describe almost anything city planners may have found problematic or offensive with the city structure. Often blight was used to describe otherwise healthy urban neighborhoods inhabited by a single ethnic group; historic and dilapidated buildings whose owners were either uninterested in renovation or unable to secure funding to do so; heavy, poor, or inefficient traffic flow through central business districts; and nearly any other sociological or psychological issue that was affecting the urban area. A blunt instrument, “blight” provided ready justification for planners’ redevelopment aspirations in the postwar period.

A consequence of ongoing urban flight was a diminishing cost to obtain urban properties. Owners eager to sell and begin life anew in the suburbs reduced prices for their downtown real estate, which allowed people (most often racial and ethnic minorities) to move into these areas. Communities soon began to spring up centralized around local structures such as corner stores, with strong ties of both cultural identity and place of origin. Under most urban renewal plans in the 1950s and 60s, these places were referred to increasingly as “slums.” As part of urban renewal, cities were provided with federal funding to acquire slums and blighted areas and clear the land, which was then handed over to private developers. Under the revised act in 1954, developers were also to be provided with FHA-backed mortgages, among other incentives.2

Urban renewal could be described as an outgrowth of modernism by way of the utopian visions of city planning popularized by Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, among others. Though their schemes – seen most famously in Le Corbusier’s “Contemporary City for Three Million Inhabitants” with its emphasis on “towers in a park” and in Wright’s suburban, low-density “Broadacre City” – were inherently different, both celebrated the machine in design principle and functionality, almost regulating the human aspect of city planning to an afterthought. Large civic spaces were common, as were centralized government buildings and, in Le Corbusier’s case, large apartment blocks for dense urban living and a dependence on the tabula rasa approach. Le Corbusier’s scheme was as decidedly European as Wright’s was American and, in many ways, Albuquerque at first followed the Wright model, centered on the automobile and large suburban plats for housing. While the city was too arid to represent the suburban farming condition Wright held in such esteem, it did allow for sprawling development. It was this development that had begun to drain downtown of its population. In time, officials shifted decidedly toward the Corbusian model, with an increasing emphasis on clearance and monumental redevelopment downtown.3

1965 Central Area Study

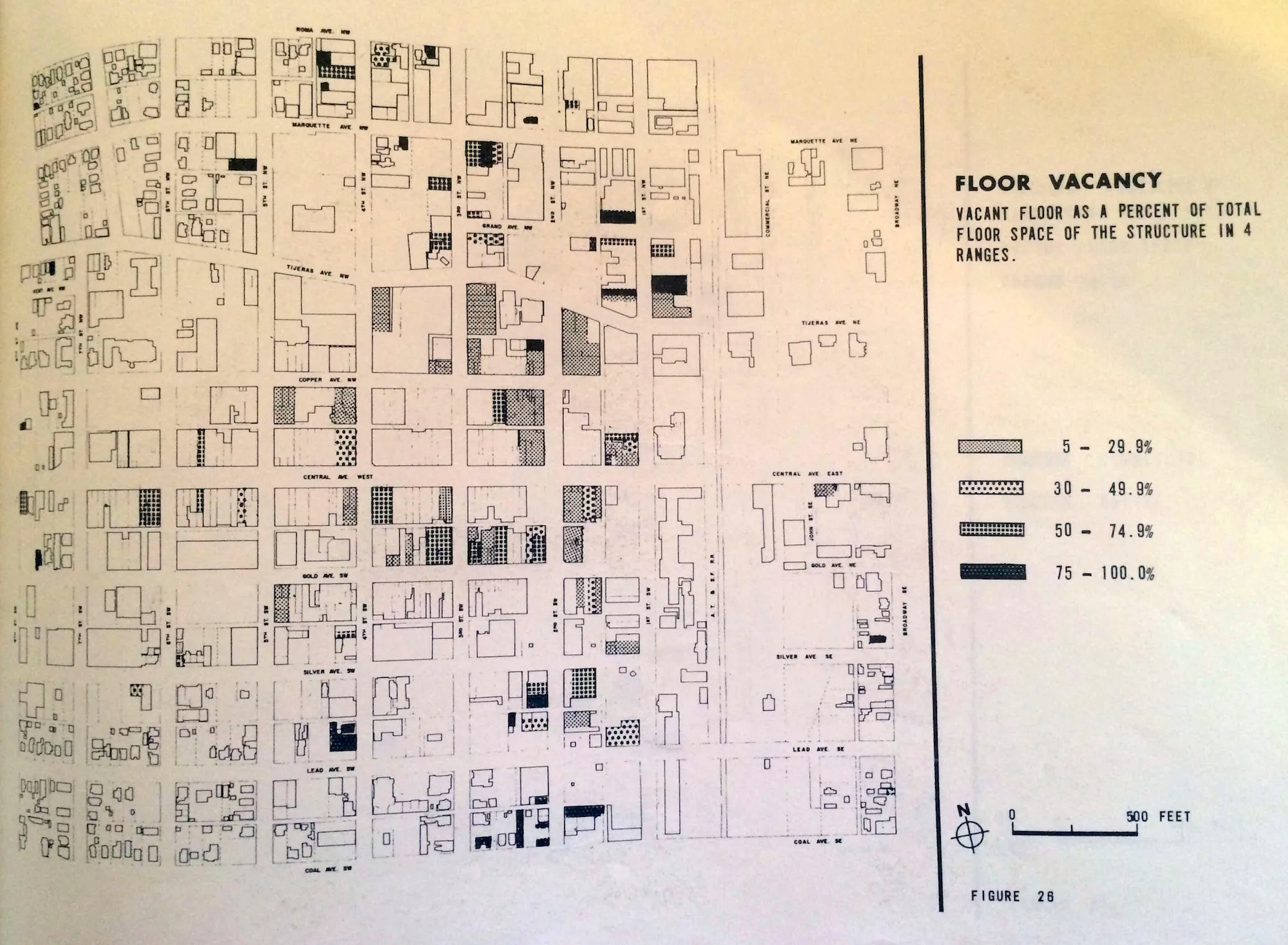

This shift came from the changing state of the CBD, at least in the eyes of planners. According to the 1965 Central Area Study, carried out by Albuquerque’s planning department, in the blocks immediately north and south of Central Avenue the vacancy rate was less than many other contemporary cities—an average of about 25%, with nearly all of that concentrated in office buildings. This was hardly surprising, given that the tenant roster for such buildings usually included doctors, dentists, and lawyers, many of whom had found more convenient access to their clients near the developing Northeast Heights. However, the same study found that only a little over half of the structures within the CBD were in good to excellent structural condition, due partly to age and partly to neglect. Circulation was also poor through the CBD, restricted by a city grid designed for carriages and trolleys, not the automobile, and alleys too narrow to efficiently restock stores and businesses, resulting in street space being used for this task. In addition, Interstates 25 and 40 bypassed the CBD and relegated this former commercial center to a sleepy outlier. The general feeling was that Albuquerque’s downtown was shabby, old fashioned, and plagued with poor circulation, inconsistent building use, lack of private redevelopment, and declining business. City planners enumerated this list of problems, loosely referenced as “blight,” in their Central Area Study.4

Albuquerque differed from many urban centers in several important ways. Even as it experienced a population boom unprecedented in its history, the size of the metropolitan area was significantly smaller than other cities in the region, such as Dallas or Phoenix. The city government also initially turned away from the idea of urban renewal supported by federal monies, due in large part to their preoccupation with expanding the metropolitan boundary via annexation, but also due to the political machine operating in Albuquerque at the time, helmed by Clyde Tingley, who effectively served as the city’s mayor into the early 1950s and would have been unable to manipulate federally-funded, housing-based redevelopment to further his own political ends. The lack of state enabling legislation and a formalized housing code also skewered early talks of urban renewal.5

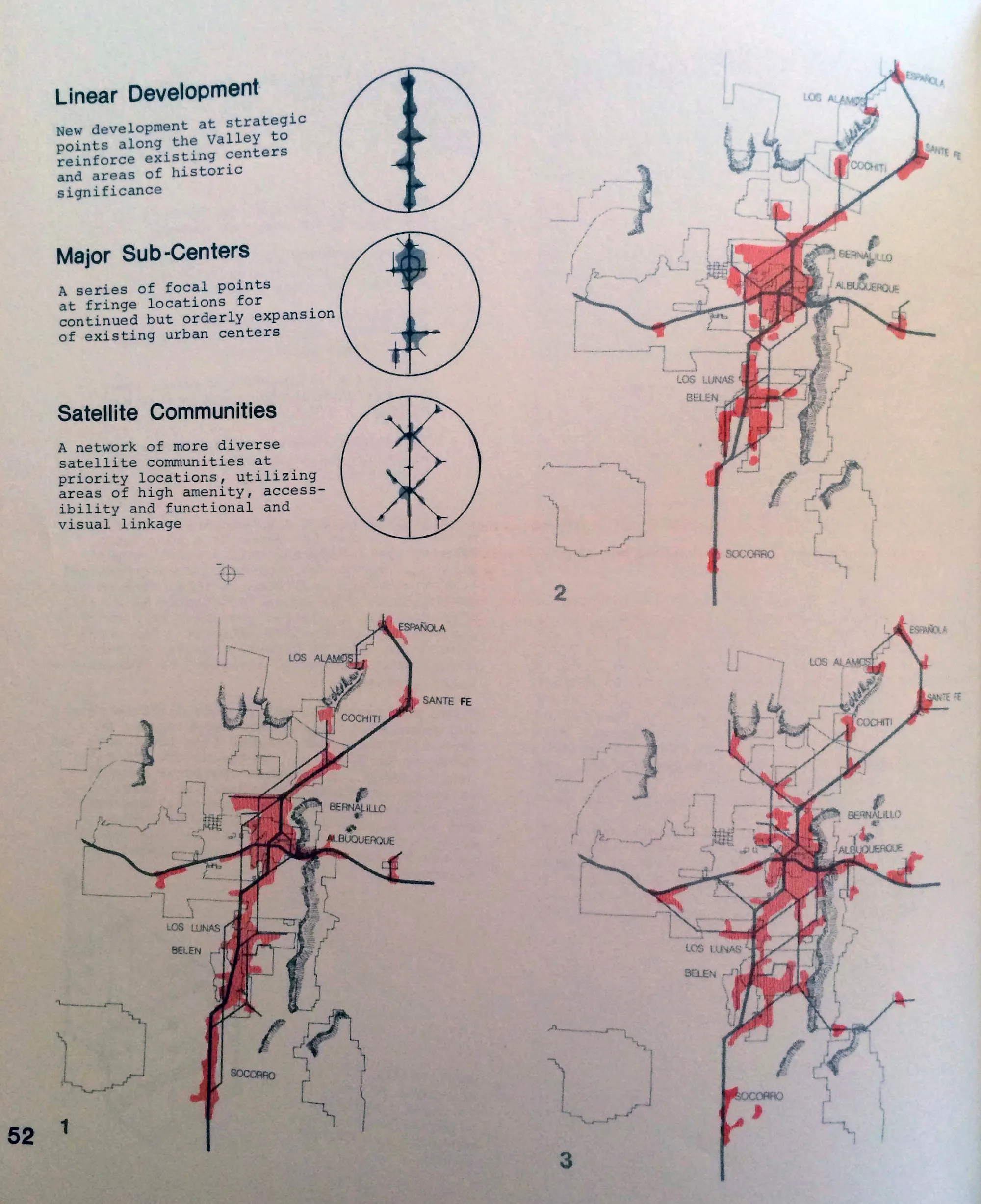

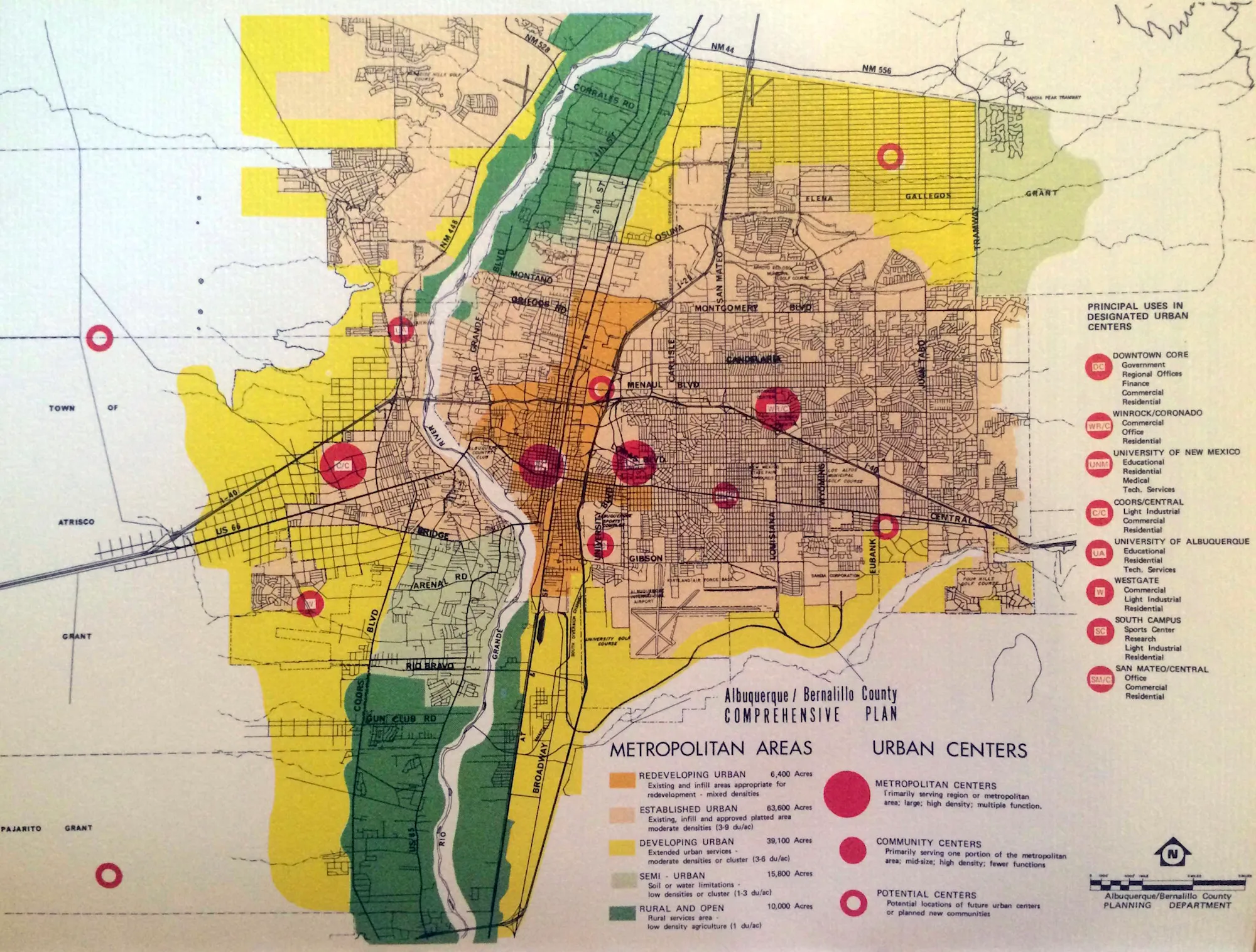

By the late 1960s, however, it had become harder and harder to deny that downtown was no longer a bustling place, and that its shabbiness had slowly given way to dilapidation. Dense neighborhoods north and south of the CBD were beginning to look less well kept than in years past, and further growth in the Northeast Heights and on the West Mesa continually shifted the geographic center of the city.6 That sprawling growth also undermined new private downtown development. Venture capital was “[more] difficult to raise for the CBD than… for investment in other parts in the city because many have the attitude ‘you can’t fight the progress’ and then invest elsewhere,” to quote the Central Area Study. City planners also focused increasingly on a multicentered understanding of regional development, casting predictions as to where the city would become more urban in the future.7 Downtown was lost in an uncertain time; officials hoped to rediscover its role in the changing city.

Tijeras Urban Renewal Project

As a result, city leaders became more amenable to federally funded urban renewal. In 1968, Albuquerque received $25 million for what would become known as the Tijeras Urban Renewal Project. Covering 182.6 acres in and near downtown, this plan focused on the neighborhoods north and northeast of the CBD – around Tijeras Avenue and the low-numbered streets, north to Lomas Boulevard and east to Broadway Boulevard – rather than the Central Avenue corridor itself. A major facet of the plan was the rehabilitation of suitable single-family units and construction of high-density housing developments on cleared property. Resident reaction to these disruptive proposals was swift and negative, with mounting pressure placed on the city government to change their plans. Frustration also grew in response to the plan’s own flawed assumptions. Most notably, a neighborhood slated for demolition and listed as a “slum” was in fact split between run-down homes and well-maintained ones built at the turn of the century.8 Foreshadowing this opposition, voters had rejected several bond issues relating to the Tijeras plan even before it appeared as a whole. Residents refused to vote in favor of the $2 million Hall of Justice and a $750,000 museum building. They did approve $20 million worth of civic improvements, however, including an overpass into downtown, improving circulation through the area.9

The scheme for the Tijeras Urban Renewal Project conformed more closely to modernist principles than those that followed it. It was in many ways a top-down approach, focused on ways the government thought that people should live and where that should happen. Herding large groups of people into housing complexes was a common approach to tackling slum conditions, as seen in Chicago and St. Louis, and offered on a smaller scale here. Moreover, a vast civic plaza was to form the centerpiece of this scheme, another common modernist gesture that depended on clearance of inhabited land and offered a controlled space for the population to congregate.

Amidst the setbacks associated with the Tijeras plan, development of a successful urban renewal proposal proved an ongoing process. Planners quickly reworked their initial plans in response to negative reactions, publicizing a new plan in 1970. This comprehensive strategy turned the focus to the CBD. Centered on the area around Central Avenue between the railroad, 10th Street, Gold Avenue, and Copper Avenue, with extensions further north and south, the plan emphasized the need to create a new draw for downtown, something to revive the decaying city center. By re-centering the CBD in Albuquerque’s urban fabric, city planners hoped to further the rehabilitation and redevelopment of other sections of the metropolitan area, which would create a citywide trend of revitalization. The city’s research informed the formation of a list of objectives to be met by this new plan:

- To develop downtown as the leading metropolitan center of the Albuquerque region.

- To create a downtown that caters to the pedestrian.

- To provide a variety of spaces within downtown for changing needs and activities.

- To promote a higher density and better quality of urban residential areas.

- To develop efficient and distinct systems for moving people and goods.

- To develop a sense of place and identity for downtown through gateways.

- To preserve architecturally interesting and/or significant buildings.

- To stimulate interaction between government and citizens to form a better functioning downtown.10

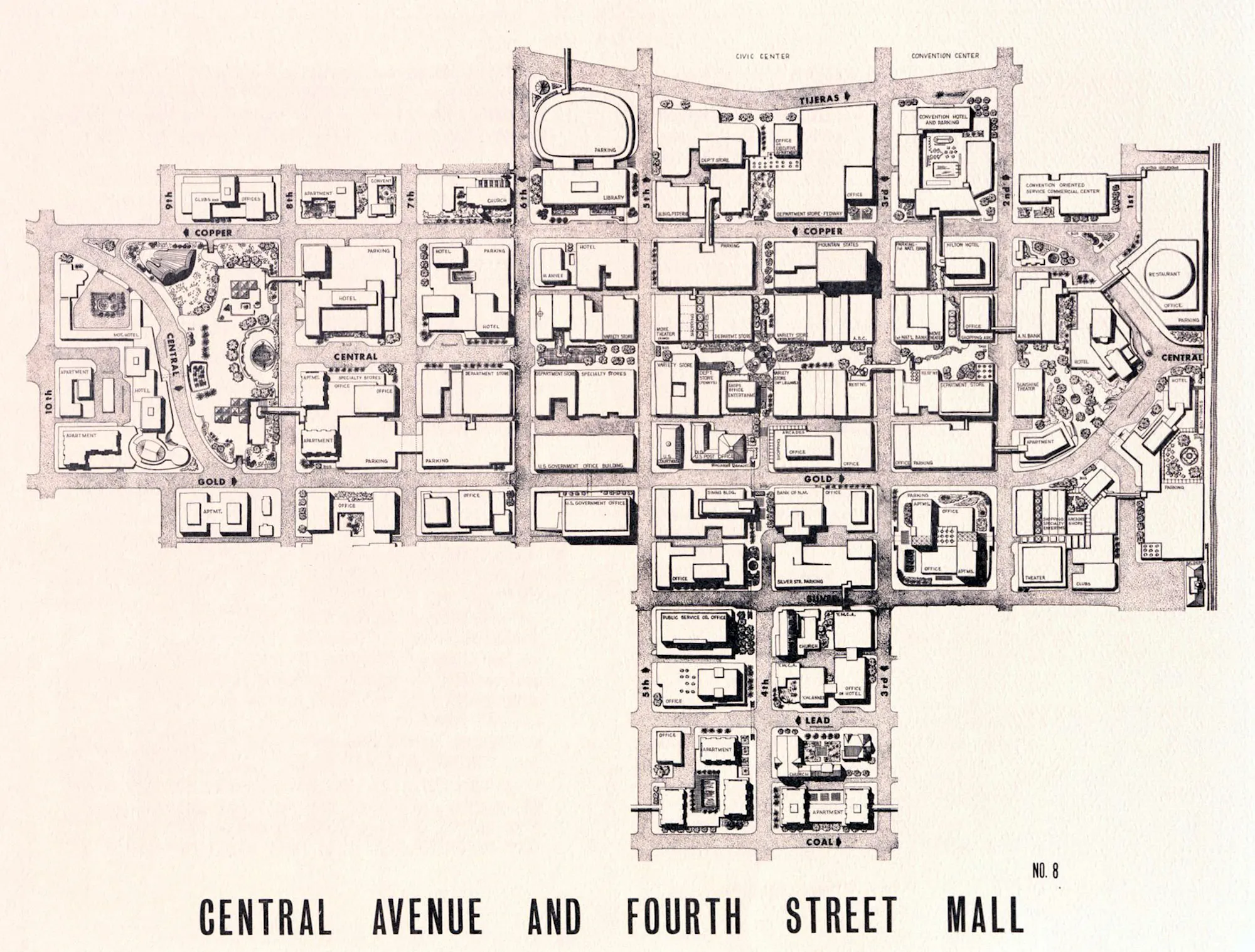

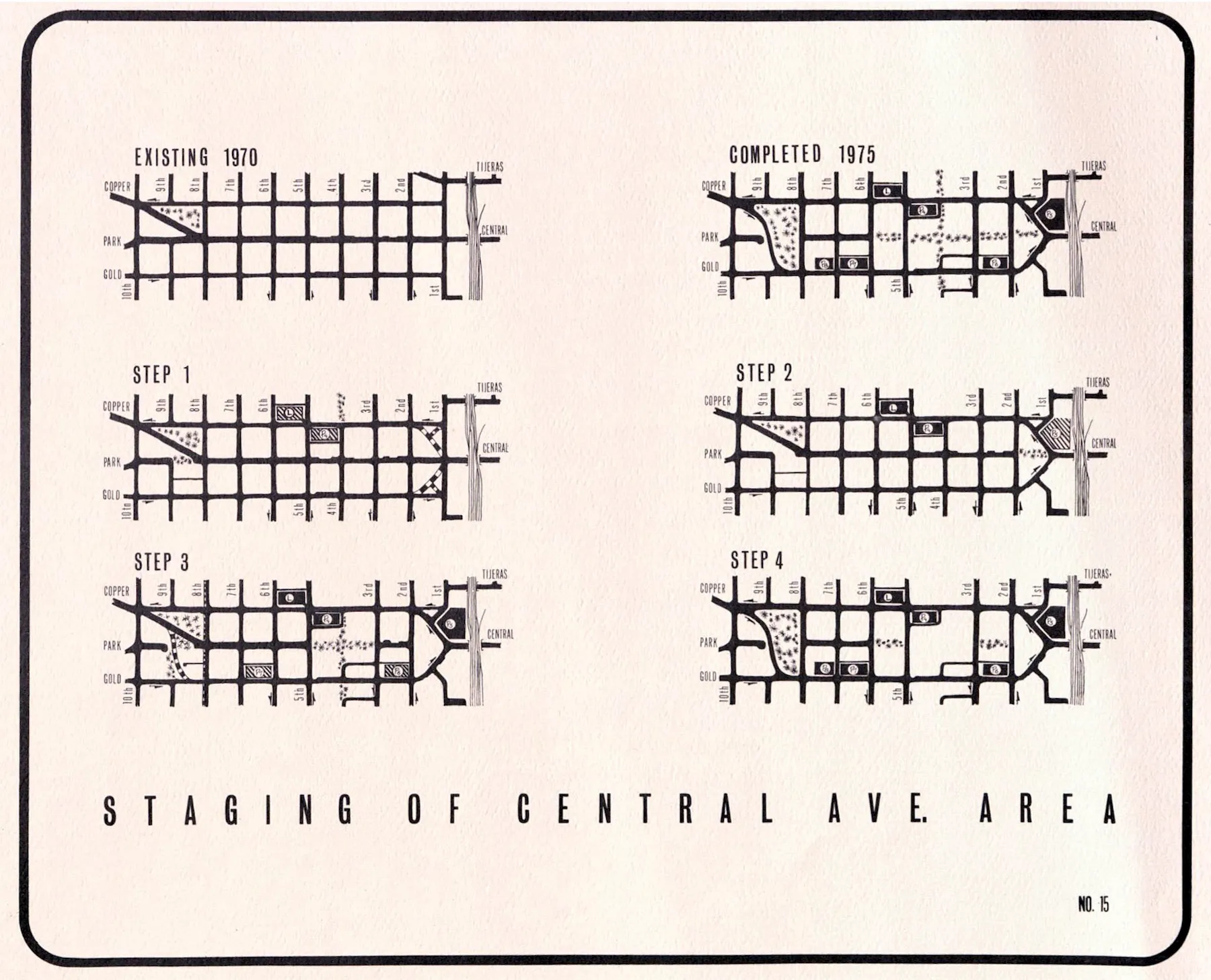

These goals, joined together, resulted in one main draw—the Central Avenue and Fourth Street Mall, a pedestrian-only redevelopment of Central Avenue between First and Seventh Streets that decidedly tapped into new suburban commercial typologies as part of its inspiration. Planners anticipated that new construction and renovations to buildings fronting Central Avenue along this corridor would result in large new retail spaces housing five proposed department stores, three variety stores, a movie theater, and three hotels. This redevelopment would rearrange the street grid, with the traffic flow on Central diverted north and south to Copper and Gold Avenues, turning those streets into one-ways parallel to the redevelopment.11

Yet another draw emphasized in this plan for downtown was a new convention center, intended to attract dozens of profit-generating shows and conferences to the city. Additional department store space, in this case intended for Fedway, was to be located next to the new convention center, along with a convention center hotel complex. The proposal for a large civic plaza remained in these revised plans. It was to be fronted by government and institutional buildings that would invite community interaction with city officials. Apartments and office buildings placed throughout the plan provided ideal centralized living, offering up a short commute to work, shopping, and recreation. Many of the existing architectural gems along this corridor were to be preserved in the plan, including the Hotel Franciscan, Albuquerque Hilton, National Bank Building, and the Sunshine Theater. Implementation would take place over five years, with the street grid modifications completed by 1975, setting the stage for the rest of the development to begin construction around the altered grid.12

This vision undeniably suggested that downtown could maintain its historic role as a center for residence, commerce, and business, despite the miles of new development still booming on its edges. City planners readily recognized this edge development would not stop for decades, and instead of fighting that sought to capitalize on it by simultaneously injecting new development into the downtown core. Further in-depth studies conducted in 1972 expanded the list of goals presented in the 1970 plan and elaborated on them, indicating that the city had begun to understand the necessity of working with the communities that renewal would affect. This encompassing list included population growth, economic expansion and unemployment reduction, tourism promotion, an integrated transportation system, an efficient welfare system, cultural preservation, a lifelong learning environment, and promotion of recreational activities, among others.13

In contrast with the modernist goals of 1960s-era plans, the goals presented in the city’s 1970 plan leaned increasingly towards a postmodernist way of thinking, which refocused onto the individual level and reaffirmed the idea of the importance of self. This plan was not monumental or imperialistic with its goals. It did not demand the attention of the viewer, nor did its proposed interventions take an intimidating scale. Instead, it focused on intimate, natural spaces, carved within the urban fabric, designed to reverse population migration and reinvigorate civic responsibility. The plan borrowed extensively from its local and national predecessors, which embraced ideas of renewed middle-class urban living and centralized planning generally characteristic of modernist planning theory. At the same time, the city’s early 1970s plans did away with modernism’s deification of the machine by turning the car away from the city’s central spine and relegating it to the outside of the core, and likewise by rebuking ideals of a common solution for everyone by creating spaces that would remain fluid and adaptable to users’ needs.

Outcome

However idealistic or well informed the 1970 plan may have been, ultimately it remained incomplete. Officials did modify the street grid in accordance with the plan, blocking Central Avenue and rerouting traffic, and also completed construction of the new convention center. A new tower for Bank of America came into being along with a convention center hotel, as did the first in a series of civic plazas, set across from the convention center complex on recently cleared land. Yet the city did not realize other key aspects of the plan. None of the five proposed department stores were built, the proposed movie theater did not come to fruition, and variety stores themselves went out of business. Many parcels fronting Central Avenue had been cleared in preparation for redevelopment that never came, creating gaps in the city’s traditional spine and reducing downtown’s vitality. Historic structures such as the Hotel Franciscan fell to dynamite or the wrecking ball, undermining the architectural cohesion of the area. The urban neighborhoods surrounding downtown became more sparsely populated as the suburbs beckoned, inviting speculative redevelopment which only did further damage to the urban core.

The most likely aspect of the failure of the 1970 plan was squabbling among the government bodies that had their fingers in the city’s urban renewal pie, though blame could also be assigned to a lack of funds, the energy crises of the 1970s, stagnating development in the face of continued suburbanization, and a changing vision of the city’s future. Whatever the case, the partially completed redevelopment of downtown created a place that was even less friendly than before, and in fact succeeded in driving people away from the area at an ever faster rate.

It has only been in the past decade that the damage done by the incomplete 1970 plan has started to reverse. New retail space, a movie theater, the reconstruction of the Alvarado Transit Center, the newly completed Anasazi apartment tower, efforts to enliven Civic Plaza, and other recent development has filled in the pock-marks left on the city by careless demolition and haphazard rehabilitation. Time will tell if this salve will be enough to cure the reputation downtown earned in the intervening decades as an unfriendly, dangerous place to be, hardly the goal of the city’s mid-century plans. Future decades will show if the national trend of renewed interest in downtown living, which Albuquerque officials had hoped for since the early 1960s, will reach these streets.

Footnotes

-

City of Albuquerque Planning Department, Central Area Study (Albuquerque: City of Albuquerque Planning Department: January 1965). ↩

-

See Housing Act of 1949, Public Law 81-171, 81st Cong., 1st Sess. (15 July 1949); Housing Act of 1954, Public Law 83-560, 83rd Cong., 2nd Sess. (2 August 1954). ↩

-

See Robert Fishman, Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century: Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982). ↩

-

Central Area Study. ↩

-

Robert B. Fairbanks, “The Failure of Urban Renewal in the Southwest: From City Needs to Individual Rights,” Western Historical Quarterly 37, no. 3 (Autumn 2006): 303-25. ↩

-

David A. Crane and Associates, Quality in Environment: An Urban Design Study for the City of Albuquerque, New Mexico (Philadelphia: David A. Crane and Associates, February 1970). ↩

-

Crane; Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Planning Department, Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Comprehensive Plan: Metropolitan Areas and Urban Centers Plan (Albuquerque: Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Planning Department, April 1975). ↩

-

Michael F. Logan, Fighting Sprawl and City Hall: Resistance to Urban Growth in the Southwest (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995). ↩

-

Logan. ↩

-

City of Albuquerque Planning Department, The Downtown Plan (Albuquerque: City of Albuquerque Planning Department, December 1970). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Planning Department, Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Comprehensive Plan (Albuquerque: Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Planning Department, April 1972). ↩