1958

Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn

Case study by:

Alexa Murphy,Fri Oct 09 2015

Acoma Elementary School

Introduction

Acoma Elementary School is located at 11800 Princess Jeanne Avenue NE near Juan Tabo Boulevard NE in Albuquerque. The Albuquerque Public Schools (APS) financed the single-story school in the 1950s, hiring the now-defunct architectural firm Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn as designers. Acoma Elementary was one of many new schools built by the city in the postwar period to support suburban growth on newly annexed land in the swiftly expanding city. It consisted of a cast-in-place, tensioned waffle slab foundation and a roof that sandwiched masonry and steel stud partitions. These defined a space organized into a grid of 22 classrooms, administrative offices, a multipurpose “cafetorium,” and various support spaces. The school has served families living in the Princess Jeanne Subdivision since its completion in 1958; the district boundary aligns with the subdivision south of Indian School Road NE and north of Constitution Avenue NE, between Eubank and Juan Tabo. For over 50 years, Acoma Elementary has boasted a striking form: low-slung with minimal and elegant features defining a modern aesthetic; one of its most dramatic aspects is the continuous clerestory glazing that creates the illusion of a floating roof. When looking at the building in the context of Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn’s body of work, one wonders why they designed a school that looks so similar to their other projects of the same period, such as the Rio Grande Pool, that claimed such different programs. These similarities in the design of Acoma Elementary indicate the intentional repetition and experimentation necessary to create a modernism tailored to the context of the growing postwar Southwest.

Formal Characteristics

Site

Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn designed Acoma Elementary to support new housing at the Princess Jeanne Subdivision. Promotional pamphlets indicate two different potential sites for Acoma, the “newest” elementary school in Albuquerque, as Dale Bellamah developed the design of the subdivision. These commercial materials characterize the school as an amenity supporting development of community in a new suburb.1 As the city itself explained in 1960, establishment of an elementary school was key to the larger goals of subdivision planning:

The most usual current solution to the problems of designing a balanced residential area is intimately related to the elementary school. The size of the neighborhood depends on the population necessary to support such a school. All other community facilities are then calculated from this.2

The planning document’s author continues, explaining that new roads accessing all new city schools should be designed to serve a high-traffic volume, with other surrounding neighborhood roads likewise organized around the school. New schools were central to establishment of postwar neighborhoods. Acoma Elementary is an artifact of this trend, and was designed to be the center of social life in the new subdivision. In this way, among others, developers and city officials worked together to foster Albuquerque’s massive growth in this era. In the case of Acoma Elementary and Princess Jeanne, Dale Bellamah was both the developer and a member of the planning commission during the 1950s. The partnership between private real estate interests and the city of Albuquerque was essential to midcentury urban development.

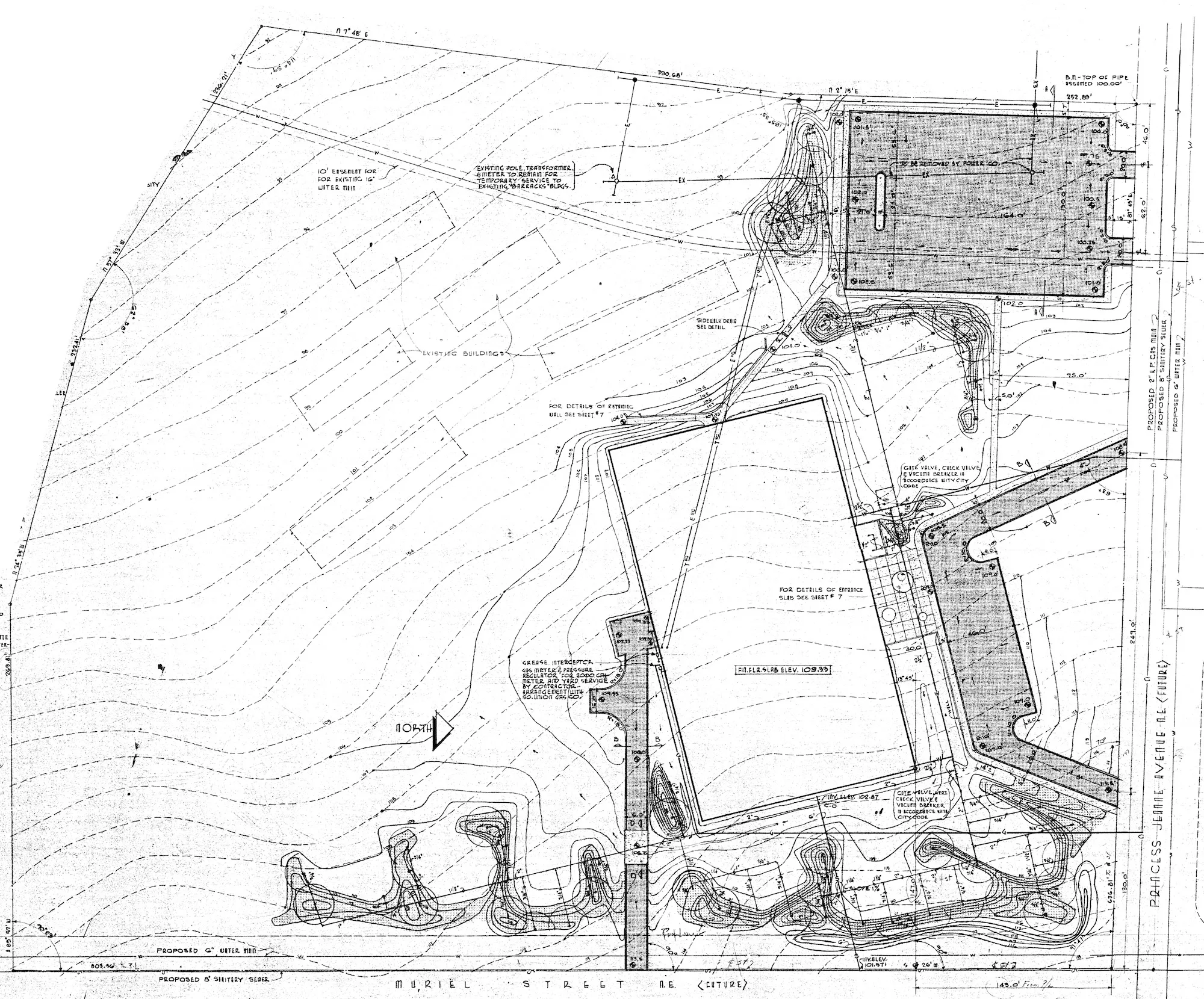

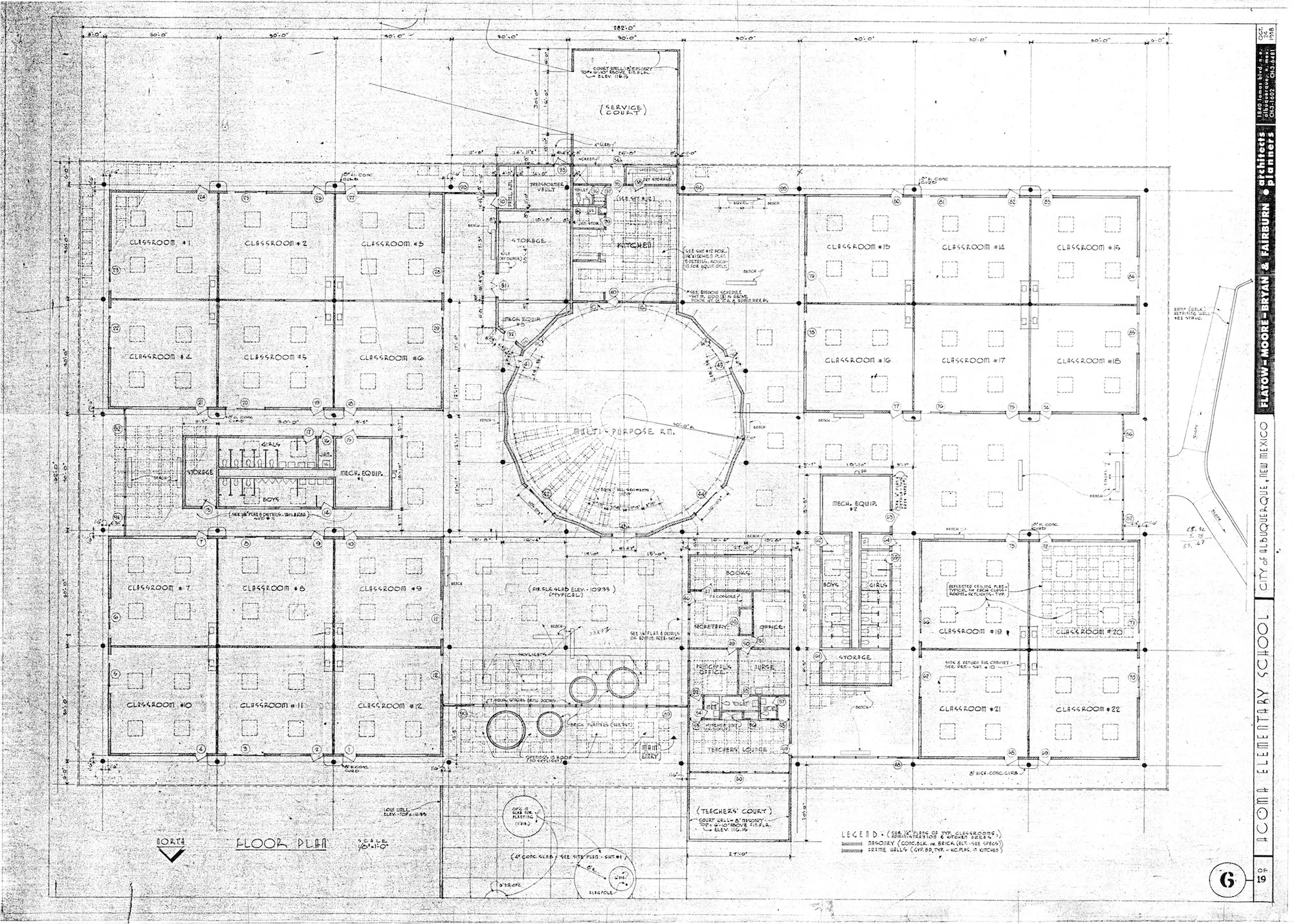

Acoma Elementary’s backers chose a generous site for the school, with single-family housing at its boundary. As Flatow’s firm designed the project for this location, the main entry faced north, with a shared bus and student drop-off loop and visitor parking connecting to Princess Jeanne Avenue NE. Staff parking was separated at the northwest corner of the site. A dedicated service drive with a waste enclosure lay south of the school, and connected the kitchen to Muriel Street NE. Drainage retention ponds ran the boundary between Muriel Street NE and the remainder of the school property. One leg of a small Y-shaped walk connected teacher parking to the school’s side entry; the other leg connected the school to open play fields for recess. “Barracks” are also indicated in the site plan, aligning with the natural site grade, and were likely used as temporary portable structures to serve students already living in the neighborhood prior to the school’s completion. No basketball courts or other play areas are indicated in the original site design. This large site was likely selected to allow for potential school expansion in the future, suggesting a vision of a neighborhood that would keep growing.

Height, Elevation, and Structure

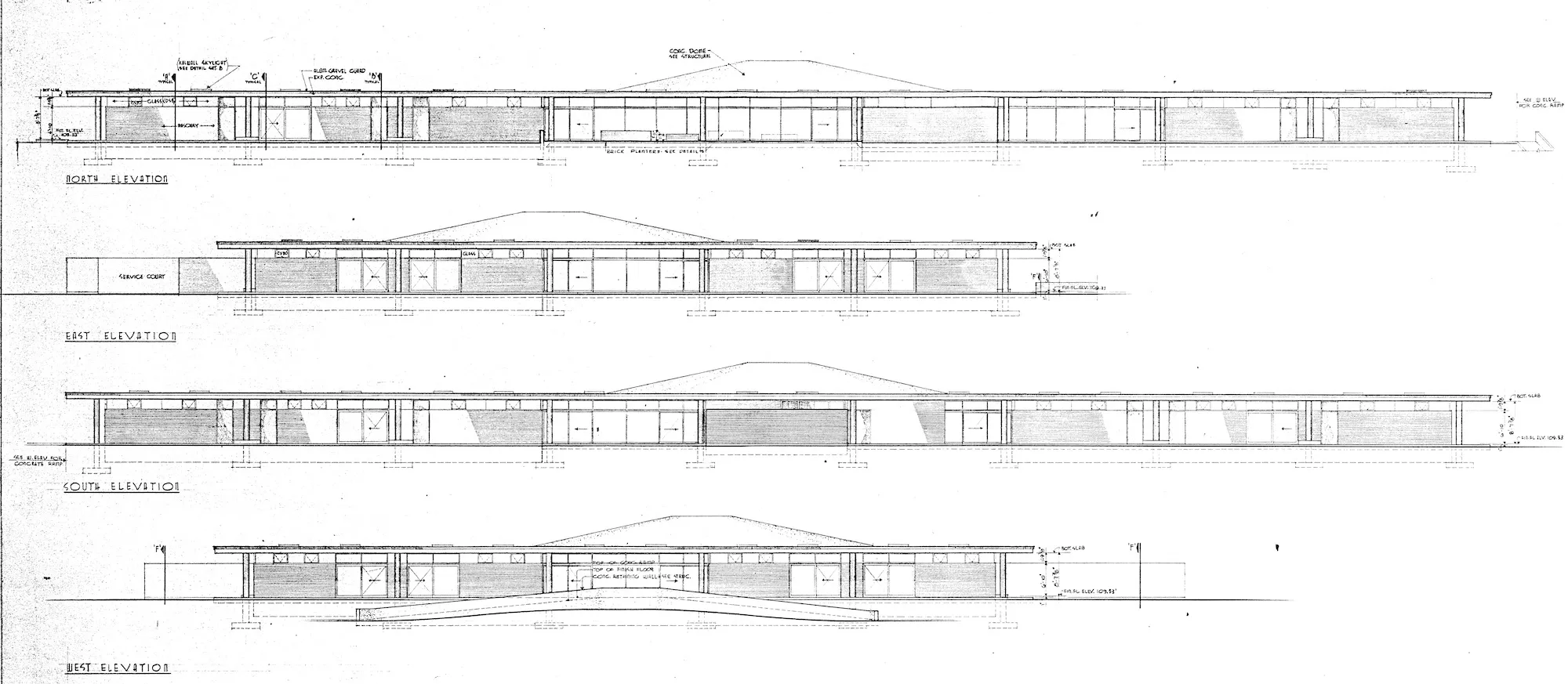

The school was, and remains, a single-story structure on a cast-in-place concrete slab. Flatow organized its spaces on a 30-by-30-foot grid of steel columns supporting a concrete roof, also cast in place, with a deep overhang reducing direct solar gain on uninsulated walls. Exterior masonry walls are liberated from the structural grid and act to divide spaces, a role likewise played by interior stud partitions. Interior and exterior walls terminate at continuous clerestory glazing at the roof, giving the roof a floating effect. Exterior columns stand apart from the wall, exposed beneath the roof overhang and defining the open-air circulation corridor outside the building. Complimenting the clerestories, skylights punctuate the roof slab between sub-grids with rebar and allow for natural daylight in classrooms but few views. The simple concrete sandwich that defines the structure is an inexpensive system using technology contemporary to the era.

Program

Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn designed the school with a simple cruciform-shaped organization. In their scheme, the main corridors intersect at the round cafetorium, at the building’s center. The cafetorium was a new design feature typical in midcentury elementary schools born out of thrift, combining multiple large programs – cafeteria, auditorium, and gym – into one multipurpose space. In addition to reducing building material, the cafetorium’s efficiency minimized conditioned space and annual maintenance costs. However, like other artifacts of modernism’s interest in efficiency, cafetoriums fell out of vogue as users discovered that spaces designed to fulfill too many programs often failed to meet any of them completely. Kitchen and service delivery areas stand south of the cafetorium. At the north end of the school is a large glazed main entry flanked by library and administration offices on either side. Large round planters on the exterior continue into the interior space, creating a transitional and modern entry. Student restrooms with mechanical support rooms bisect two of the main corridors into smaller areas. Concrete benches in the larger halls create informal gathering and learning areas for students, intended to support new, mid-century curriculum delivery methods.

Officials and Flatow’s firm based classroom organization on a variation of the “California” plan that was gaining traction at this time.3 The typical “California” plan consisted of several classroom wings similar to those at Acoma, however they were traditionally totally separate buildings connected to main administrative offices and other shared functions with covered outdoor walkways and open air courtyards. This school typology gained traction in the era of postwar suburban expansion, since school districts could save on construction and maintenance by removing corridors and extra support areas, thus reducing heated space. APS oversaw the construction of many schools of this type during the 1950s and 1960s, yet Acoma was unusual because typical “California” plan components were organized here as one contiguous building. Flatow incorporated design standards and trends in a manner that resulted in a unique interpretation that elevated the school above its contemporaries.

Interiors

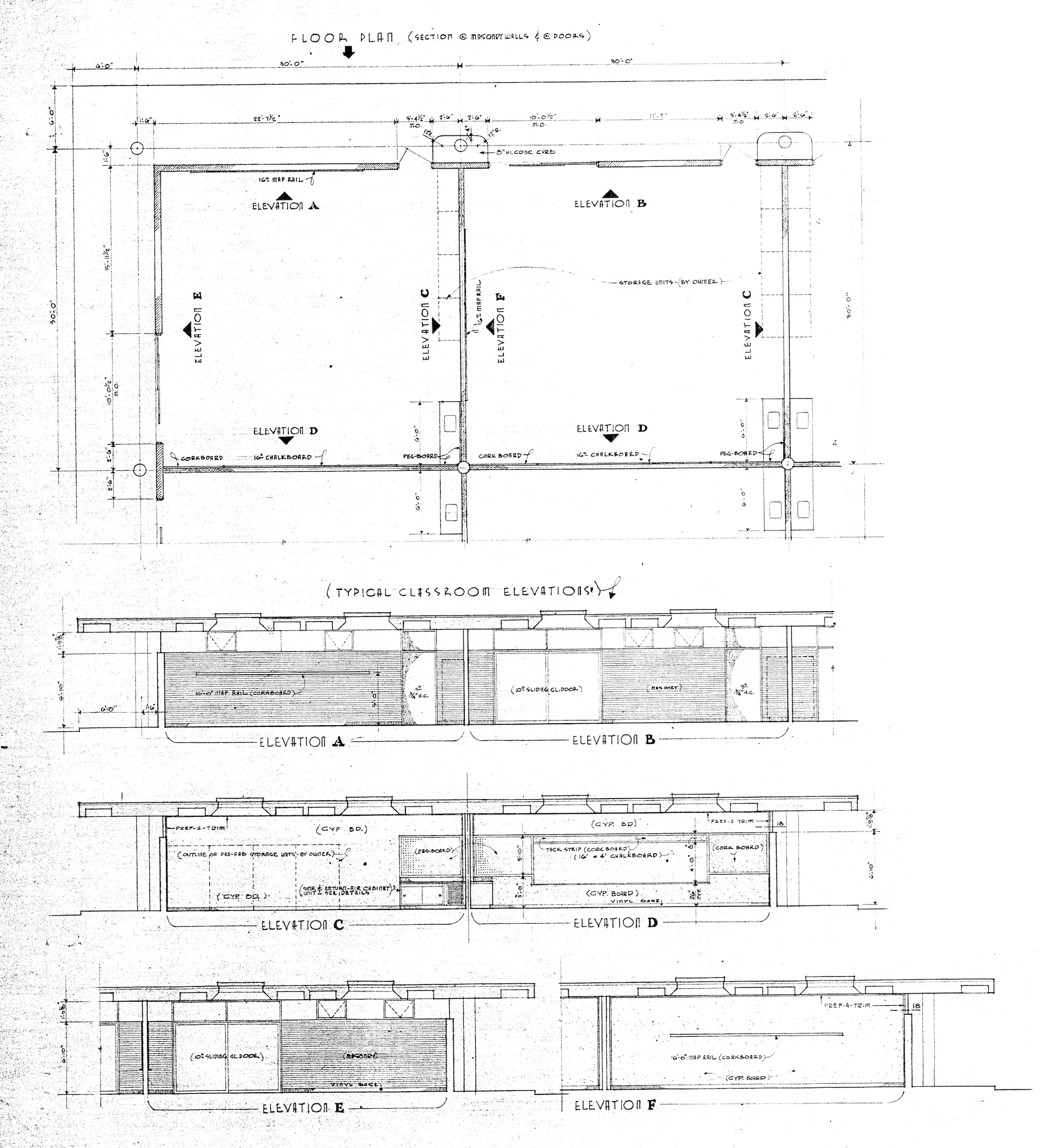

Structural systems are exposed in the majority of spaces at Acoma Elementary. Flatow’s intention was that these elements would not be perfunctory and hidden. Instead, he saw them as an integral part of the design, as evidenced by their inclusion in interior elevations. These drawings are unusual by the normal standards of documentation because they extend the view past the wall surface enclosure, cutting through partitions to the exterior spaces. They include abundant sectional information to communicate the idea that interior spaces have important relationships with the exterior, mediated by structure, walls, and roofs. The application of interior finishes in the school is spare, typical, and intended to improve maintenance: vinyl composition tile (VCT) covers the floors, while interior gypsum surfaces and steel details are painted. Instructional surfaces like chalkboards and tack strips display student work and align with grout lines at exposed masonry walls. Built-in storage casework is sparse, and includes return air grilles that connect to the slab system. Ceilings are open with exposed structure. The spartan application of finishes shifts the focus to carefully integrated structural design encompassing space and light. Acoma Elementary’s minimal elegance moves beyond mundane efficiency to create a modernist aesthetic.

Context and Style

The minimalism of this building is key to its identification as modernist. Acoma Elementary stands as a product of the trial and error through repetition that was necessary for the development of both new school typologies and a style of postwar public architecture characterized by thrifty simplicity.

Regarding school typology, New Mexico has a relatively long history of standardized prescriptive documents outlining school building requirements that capture the predominant approach of different eras. One such document was circulated in 1920, and included suggested designs in the Territorial style, beginning with Adobe one-room schoolhouses.4 These documents evolved through the completion of Acoma in 1958, toward the School Building Guide of 1965, a standard developed by the state Department of Education in Santa Fe in collaboration with school superintendents, engineers, and architects across New Mexico. The guide augments national and state building codes and includes suggestions for program, systems, site, and circulation.5 Zimmerman Library at the University of New Mexico holds several books purporting to offer the most efficient space planning, systems, and material options for new schools tested by engineers, including the “California” plan that became so popular in Albuquerque. Many of these books were donated from the private collections of area architects who were active at mid-century, indicating a local interest in national trends and efficiencies promised by technology, as well as the important role that school design played for Albuquerque modernists. Public education building standards have evolved over time in alignment with technology and teaching ideology; the balance between establishment of shared standards and unique requirements of place remains delicate. Repetition is key to the creation of school typology: architectural form is continually tested through use, and ideally successes proliferate while failed approaches fall away.

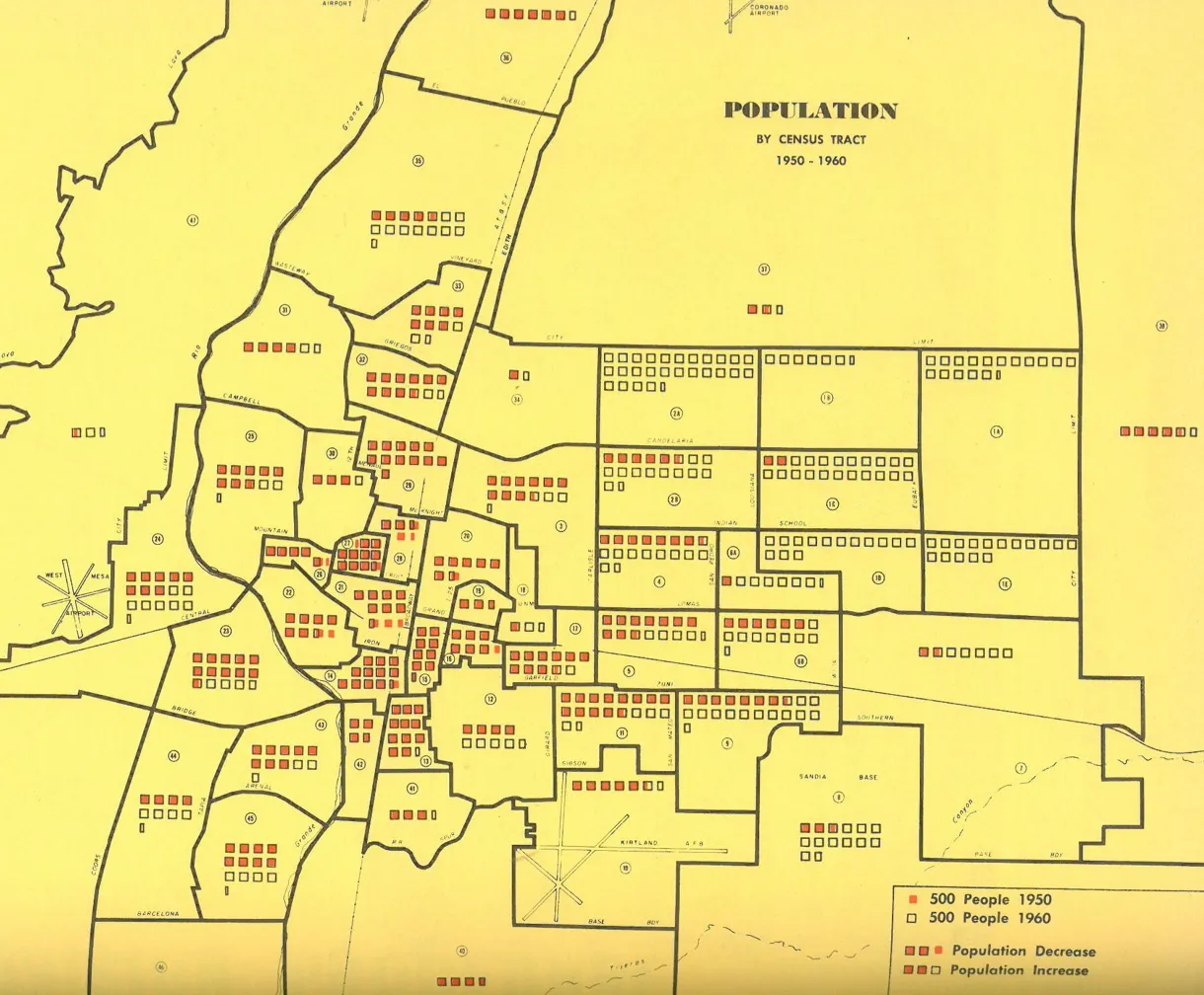

Acoma Elementary is comprised of standard school building programs, yet the building’s organization is unique and its forms and materials are more like other projects from Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn than like other area schools. Architectural historian Chris Wilson quotes leading Albuquerque modernist Don Schlegel to explain local modernism: “utilitarian function of a building in plan, material, and assembly technique should be visually stated…Materials are handled in a manner which best suits their true nature, and they are assembled so that construction techniques are clearly expressed.”6 Acoma Elementary adheres to these maxims, particularly in its unadorned expression of structural and daylight systems. Contemporary population growth may have also influenced the school’s minimalist aesthetic. Albuquerque’s 1959 Annual Report illustrates the extreme population growth that necessitated new housing and new schools. Censuses reported that Albuquerque’s population had grown 500% between 1940 and 1955.7 This growth stressed public finances due to the increased need for infrastructure to support a booming population, and probably necessitated tight budgets for new school development in new neighborhoods. These constraints and the aesthetic of the era coincided, providing an opportunity for Flatow’s firm to experiment using the simplified language that characterized their work in the 1950s.

Similarities between the structural, wall, and daylight systems of Acoma Elementary and the firm’s Rio Grande Pool, among other buildings, suggest how the architects repeated common elements across projects to develop a distinctive style. In addition to being typical of the International Style, repetition was an essential and reoccurring element in Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn’s architectural practice. For example, the First National Bank Building East tower in Albuquerque had a twin in another Sunbelt city: Phoenix. The firm’s Simms Building was inspired by Lever House in New York City, yet rooted in its local context through minor changes, such as constructing the first level with masonry reclaimed from the building that preceded it. Modernism had originated and evolved in the culture and climate of Europe and the American Northeast, both significantly different from the American Southwest. One of the legacies of Max Flatow and his contemporaries was to develop a style of modernism unique to the region in which they practiced, the Southwest. In this way, Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn did not simply copy a style, they recreated it through application of regional requirements distilled through the crucible of replication and reiteration.8 We see this in Acoma Elementary’s deep overhang that protects interior spaces from the desert sun’s harsh glare while encouraging indirect daylight in classrooms through its clerestory windows. The concrete roof structure is rooted in the heavy masses of regional architecture, but employs modern materials that still mediate solar heat gain. Likewise, the domed concrete cafetorium is reminiscent of a traditional kiva, one of the oldest building forms in the Southwest. In 1952, soon before beginning this project, Flatow summarized his contextual approach, explaining, “As to style, there is not style that is the result of chance, but always it is the concrete representation of the humanities, a reflection of intellectual, social, religious, military, and political conditions. Architectural styles are identified by the means employed to cover enclosed spaces.”9

Conclusion

Acoma Elementary remained largely unchanged for about twenty years. Though many of its overall principles remain intact today, new requirements for special education, physical fitness, and technology have resulted in alterations that obscure many of the unique features of the original building. Officials expanded the administration area with a renovation in the 1980s. They also added a detached media center adjacent to the main entry. A detached gym came later, along with playground equipment and basketball courts. The climate of concern about security caused by Sandy Hook and other recent school shootings means that the once popular “California” plan’s open campus has fallen out of favor. Acoma Elementary will likely be replaced or otherwise renovated in the near future.

Suburbanization and the nuclear family it promoted necessitated new elementary schools to serve them. Later advances in family planning and resulting social changes in the 1960s made the fundamental motivations behind these planning requirements obsolete. Although culture continues to evolve, the fundamental core of the school remains nonetheless useful, though it remains to be seen how much of this modernist project will persist in the years to come. As these schools depart from Albuquerque’s built environment, so too will the experiments in a localized modernism that they represent.

Footnotes

-

“Here’s Yours” and “Who Done It?”, ca. 1954, Box 1, Folder 1, Dale Bellamah Homes Records (MSS 646 BC), Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM. ↩

-

City of Albuquerque Planning Department, Tenth Anniversary Issue, Annual Report 1959-60 (Albuquerque: Planning Dept., 1959-60). ↩

-

“Evolution of the Form of a Traditional Building Type – the School,” Architectural Record 161 (April 1977): 125-127. ↩

-

New Mexico Department of Education, Plans and Suggestions for New Mexico Rural School Buildings (Santa Fe, 1920). ↩

-

New Mexico Department of Education, New Mexico School Building Guide (Santa Fe, 1965). ↩

-

Chris Wilson, The Myth of Santa Fe: Creating a Modern Regional Tradition (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997). ↩

-

Tenth Anniversary Issue, Annual Report 1959-60. ↩

-

Tobias Flatow, conversation with author, 7 October 2015. ↩

-

“Pueblo-Type Houses Matter of Habit, Architects Assert,” Albuquerque Journal, 3 November 1952, p. 14. ↩