1961

Victor Gruen

Case study by:

Max Boruff,Fri Oct 09 2015

Winrock Center

Grand Opening

March 2, 1961: a day that forever changed the way residents shopped in Albuquerque. The culprit: a glittering, multi-million-dollar retail complex called Winrock Center. Regarded by some as the “garden that grew money,” Albuquerque’s, and New Mexico’s, first shopping mall enjoyed four decades of profitable business before poor management and a crippled economy spelled the end for a once well-designed and architecturally wondrous commercial center.1

Prestigious History

Winrock’s story begins long before any opening ceremony. In June of 1920, the University of New Mexico purchased a parcel of land on Albuquerque’s East Mesa, with the intent of transforming it into a garden to produce vegetables for resident students.2 It didn’t take long for this idea to go fallow, and the land was left untouched for the next three decades, save for bike trails carved by children crisscrossing the 480-acre site.

Meanwhile, in April 1950, the opening of Northgate Center in Seattle irrevocably altered the American retail landscape. Though not the first suburban shopping center, it was the first of a species, a retail complex with stores oriented inwards facing a central pedestrian corridor, or mall.3 While early shopping centers were structured around parking areas, these new malls stood at the center of vast asphalt seas of parking, setting the mall as a destination, a retail oasis in a desert of tract housing. Early developers planned malls as all-in-one complexes, and many could boast low- to high-end retailers and services, including department stores, apparel, shoes, furnishings, supermarkets, drug stores, five-and-dimes, post offices, banks, and medical offices, in addition to community-oriented recreation activities, such as bowling alleys, ice skating rinks, and bandstands. Suburbanites saw convenience, but developers saw dollar signs.

This would be the case in Albuquerque too. In 1953 the University of New Mexico began selling off its 480-acre site one plot at a time to the city’s most prominent residential developers. UNM sold the first 160 acres to Ed Snow that year, and then another 160 acres to Dale Bellemah three years later. These plots gave life to a new way of suburban living in Albuquerque. Their construction of large subdivisions spurred rampant development on the mesa and caused a large population movement to this newly built part of town. This physical and demographic transformation set the stage for a retail center to be established in this area, to provide a new “core.”4 It was not a local developer, however, but a 1958 meeting between UNM president Tom Popejoy and wealthy financier Winthrop Rockefeller that set events in motion for the creation of Winrock Center (and that explains its name: Win-Rock).

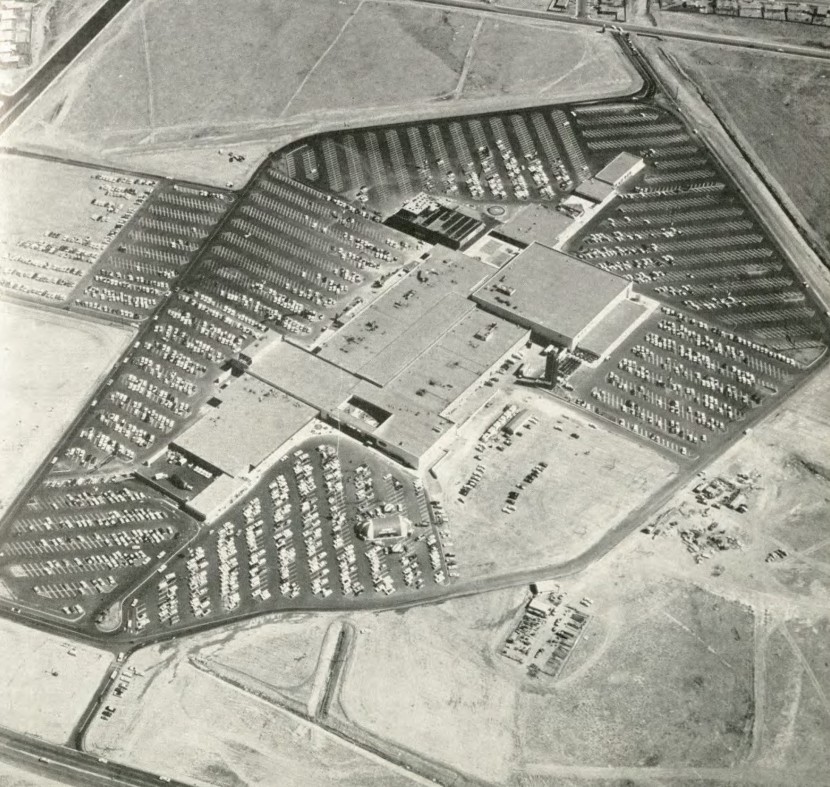

The two men negotiated a leasing agreement wherein Rockefeller would finance the construction of a regional shopping center, the “largest between Dallas and Los Angeles.”5 This complex was to be sited on 122 acres of the last of the university’s 160-acre plots. As university officials looked outside of New Mexico for the money to build this shopping center, so too did they look elsewhere for a competent architect to design it. They tasked famed mall architect and modernist Victor Gruen with designing the 500,000-square-foot mall.

Victor Gruen

A refugee from Nazi-occupied Austria, Gruen arrived in the US in 1938 with only a degree in architecture (and eight dollars) to his name. From these humble beginnings sprung his 39-year career in retail architecture, during which time he fine-tooled the concept and function of the shopping mall, influenced urban redevelopment, designed European-inspired downtown shopping centers, and even shaped the way we buy merchandise inside the mall.6

Gruen’s glitzy Glendale Center in Indianapolis had just opened in 1958, and no doubt impressed Rockefeller and Popejoy. Indeed, Gruen’s extensive resume included some of the earliest malls in the country, such as Northland Center in Southfield, Michigan (1954), Southdale Center in Minneapolis (1956), and Eastland Center in Detroit (1957). These complexes showcased Gruen’s extensive skill with retail architecture and his abilities to thoroughly design a shopping center, adding to his allure.

Design

Construction of Winrock commenced in 1959 and continued through 1960, despite lawsuits from competing developers and a murder on the property, and finally finished in early 1961. With a roster of 50 tenants both new and familiar to Albuquerque residents, the complex was soon on its way to becoming a financial success.

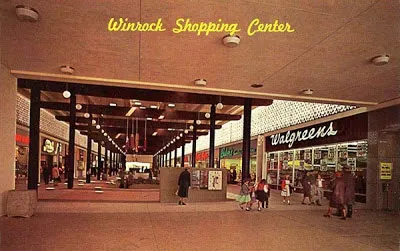

Built in a common dumbbell-shaped plan (dumbbell referring to the placement of the anchor stores in relation to the mall corridor) the original Winrock Center featured two major anchors, one at each end of the structure. A three-level Montgomery Ward anchored the southeast corner, and a one-level dry-goods-only J.C. Penney Co. anchored the northwest end. The roster of stores on opening day also included Safeway grocery, Walgreen’s Drug, National Shirt Shops, Lerner Shops, Paris Fine Shoes, Toys by Roy, Stromberg’s, Cook’s Sporting Goods, Baker Shoes, Zale’s Jewelers, and a Fedway department store. By condensing much of Albuquerque’s retail landscape into Winrock, UNM created a nexus for growth in the Northeast Heights, and influenced how much of the Uptown area was subsequently developed.

Commercial Impact

Winrock transformed Albuquerque’s commercial landscape and, likewise, offered an innovative new architectural form for its host city, though it was not the greatest work in Gruen’s oeuvre. But perhaps the blame is not his alone. Designed as a partly enclosed mall, an abstracted post-and-lintel system – a common Gruen strategy – held the canopy over the main corridor aloft, while decorative grilles over the storefronts and some 93 skylights let light and air inside. Modern sculptures such as colorful mobiles, elegant light fixtures, and fixed concrete furnishings including planters, benches, and fountains helped make the space seem less cavernous and more human in scale. This modern landscape, a canvas of simple materials with thoughtfully designed accents, was a device that Gruen employed to great effect in many of his malls. It was poorly oriented, however, and the east-to-west winds so common in Albuquerque whipped through the corridor, earning the mall the slightly unflattering nickname of “Windy-Rock.”7

A contemporary article in New Mexico Architect magazine lamented Winrock’s lack of architectural unity, a distinct feature of many Gruen-designed malls. The author of that article held Gruen’s firm accountable for not designing more of the interior storefronts, and for the “lack of inventiveness needed to express the potential of the plan” by the primary anchor stores.8

Despite its architectural shortcomings in the eyes of some, Winrock’s quick commercial success established the center as a retail mainstay in Albuquerque and, less obviously, tied it to the ebb and flow of retail economics throughout the rest of the country. The retail landscape is a strange place, with few fixtures of permanence to be found. Almost since their inception, suburban malls have been continually remodeled, expanded, and modified in an attempt to keep up with or predict consumer trends. Winrock was no exception to this rule.

In 1963 the adjacent White Winrock Motor Hotel opened as one of the few mall-attached motels in the country. The sleek lines of the structure presented a more cohesive vision than the mall it served, and an addition to the hotel, completed in 1979, maintained this cohesiveness. 1963 also brought Winrock Medical Plaza to a north mall outparcel, bringing to fruition the goal of most early malls to have a multitude of services aside from shopping as part of their roster of tenants, in order to provide an all-in-one stop for shoppers. J.C. Penney expanded their Winrock location to a full-line/new-look store in 1964, and the next year the Fox Winrock Theater opened on another outparcel.9

Competition and Expansion

An interesting development in Winrock’s history was the commercial competition of Coronado Center, which opened less than half a mile north on Louisiana Boulevard in 1965. Unusually, the two malls maintained a friendly rivalry throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, and while neither center closed as a result of competition from the other, their close proximity meant that the malls often conducted their renovations and expansions around the same time.

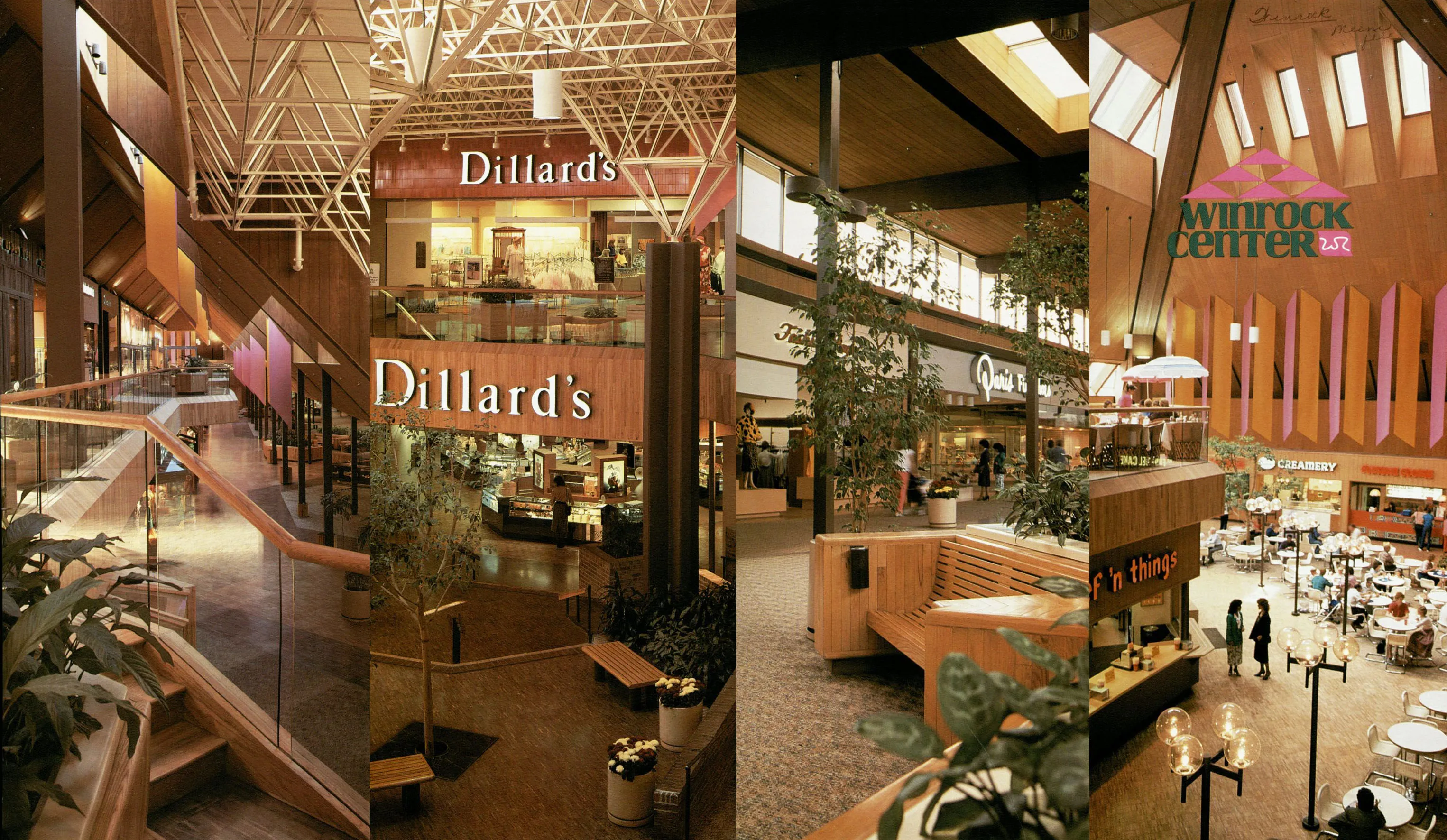

Winrock’s owners carried out its first major expansion in 1972 with the North Mall addition. Dillard’s of Arkansas had purchased the Fedway department store chain in 1971; the new owner subsequently converted Fedway’s five stores to the Dillard’s nameplate, including the Winrock location. The existing store was too small for the new tenant, so Dillard’s built a new three-level store north of the Fedway building, which gained a new tenant, Cook’s Sporting Goods. The North Mall addition connected the new Brutalist-style Dillard’s location with the existing complex.10

Coronado’s expansion and full enclosure in 1974-75 (perhaps itself a response to Winrock’s 1972 expansion) prompted mall management to enclose Winrock in 1975, which provided it with one of its most iconic features, the dramatic red pyramid over the former open-air east court. This eliminated wind issues created with the poor siting of the main mall corridor and provided a comfortable, year-round shopping experience. Contemporary pamphlets used the pyramid and Winrock sign pillars as identifying graphics, and the red metal roof soon became a local landmark.11

With the closure of Cook’s Sporting Goods in the early 1980s, the mall was left with a sizeable block of vacant space between Dillard’s and Montgomery Ward. Rather than seek a new single tenant, in 1984 mall management chose to subdivide the junior-anchor sized space into inline stores, including the second floor. They integrated this into a partial second level of retail over the North Mall. At this time, the mall also gained a new anchor store, Beall’s, and a new mall staple, a food court, located in the lower level of the Pyramid Court. New decorative elements included light blonde woodwork, taupe paint and carpeting, and new planter boxes. Photographs included in a brochure from the period after these renovations show interiors that manage to combine Gruen’s original architectural elements with these contemporary features in a surprisingly harmonious fashion.12

Positioning itself as a more upscale mall compared to the neighboring Coronado Center’s youth-oriented store roster, Winrock patrons enjoyed the mall’s quieter, more refined atmosphere, “diverse fashion appeal,” and distinct architectural style. Unfortunately, Winrock’s golden years did not last long.13

Decline and Downfall

In 1991 charter anchor J.C. Penney moved from Winrock to Coronado Center, leaving a large vacancy. In an attempt to further elevate Winrock’s status, mall management demolished the Safeway/Walgreens ell of the structure and heavily remodeled the west court entrance and former Penney’s building. By 1994, Dillard’s assumed that anchor spot with a men’s, children’s, and home store, refitting the existing store as a women’s location and establishing a “double header” operation. The remodeled Penney’s was distinctly Dillard’s, but gave no hints to either the historic modernist style of Winrock or regional architecture, and could be confused with many suburban Dillard’s locations across the southern United States. 1991 also brought the downsizing of Montgomery Ward during that company’s restructuring efforts. Management subdivided its large building, clumsily inserting a new, sky lit escalator court by the east mall entrance and tenanting the east half of that building with a Marshall’s.

Winrock’s management likewise refreshed its interiors during this period, which unfortunately did more to damage original Gruen features than anything else. New storefronts intruded upon the spacious original mall corridor and made it clumsy to navigate. The elegant post-and-lintel system holding the roof canopy became disfigured with the removal of the columns and the installation of drywall boxes over the sculptural beams. Any remaining original light fixtures were removed, replaced with turquoise neon accent lighting and common fluorescents. An unusual survivor of these drastic changes was a stone bas-relief, an art installation in the original mall relocated to the far end of the original corridor.

These were the last large-scale renovations completed prior to Winrock’s 2007 closure, but even they could not stay the inevitable. The retail landscape during the 1990s was a place of turbulent change. The migration to the suburbs was starting to reverse as cities revitalized their downtowns and urban living became popular once again. In addition, over-malling had saturated many metropolitan areas with more retail square footage than they could financially sustain. Cities like Dallas and Los Angeles claimed a glut of over a dozen malls each, numbers that would soon be halved as weak or poorly performing malls were shuttered and demolished. Many malls, including Winrock, started to decline in this period and would never recover.

Store closures at Winrock began slowly but gathered speed. The Marshall’s location closed in 1995, replaced with a Bed, Bath, and Beyond the next year. Local establishments, including Stromberg’s and Paris Shoes, closed their doors. A veritable ensemble cast of mall staples came and left the Winrock roster, with vacant storefronts increasingly lining the mall corridors. In the late 1990s management closed the deserted upper level of the mall, followed several years later by half of the food court. As early as the new millennium, with sales slowly falling but still profitable, redevelopment rumors began to circulate.

Montgomery Ward shuttered for good, along with the entire chain, in 2001. Its space never again held a tenant. In 2002 Prudential Real Estate Investors purchased the mall’s land from the University of New Mexico, and immediately proposed to redevelop the moribund structure, under the tentative heading “The Avenue at Winrock.” Following the latest retail trend, the “lifestyle center,” the proposal involved demolishing much of the existing structure and orienting new construction around two retail avenues carved through the site. Lawsuits and “rising construction costs” delayed any redevelopment from Prudential, but that didn’t stop them from issuing eviction notices to the handful of remaining inline stores.14 In March of 2007, after 46 years of business, Winrock closed.

Time had not been kind to the structure, once cleanly designed and thoughtfully planned. If one had not witnessed its evolution over time, it would be difficult to recognize the extant structure as having once been the Gruen-designed modernist landmark. As with many malls across the country, Winrock became an amalgamation of retail design trends from the preceding four decades, causing the architectural integrity of the mall to crumble.

Unfortunately, it would seem that any architectural heyday for Winrock had long passed. Prudential threw in the towel as mall owners and sold the near vacant structure to Albuquerque-based GK Partners. As the national economy teetered on the brink of disaster during the Great Recession, Winrock waited, aside from use as a film set in the 2009 comedy film Observe and Report, in silence.

Soon, the mall’s owners proposed a new redevelopment scheme, again in keeping with the lifestyle center model. Under the new name of Winrock Town Center, the majority of the existing mall, save for the occupied anchor stores, would be torn down and replaced with open air retail, office space, condominiums, and a new hotel. Renderings show a scheme that follows national trends – and those of the recently built ABQ Uptown – with little architectural invention and no reverence for the original, long vanished architecture of Winrock Center. Bulldozers soon arrived to remove the mall piece by piece. The White Winrock Hotel, closed since 2005, came down in 2012. The Stromberg’s block east of the Pyramid Court fell to make way for a new theater in 2013. Demolition day arrived for the south block of stores fronting the original Gruen mall corridor in 2015, to make way for new commercial spaces.

Conclusion

Winrock’s days are numbered. While its name may live on in the moniker for the latest retail typology, the historic structure, with its ties to a greater modernist vision and broader postwar aspirations, will be lost. As the redevelopment is ongoing and still in early stages, it is hard to tell how much of the original mall will be left, though it is doubtful much of significance will remain. It may not have been as cohesively or beautifully designed as some of Gruen’s other malls, but Winrock Center nonetheless stood as the herald of a new way of life for everyone in booming mid-century Albuquerque.

Footnotes

-

James Abarr, “The Garden That Grew Money”, Albuquerque Journal Magazine, 12 September 1978, 14. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

“Seattle’s Northgate Center,” Mall Hall of Fame, accessed 20 October 2015, http://mall-hall-of-fame.blogspot.com/search/label/Seattle%27s%20Northgate%20Center. ↩

-

Harold Benson, “It’s Fun to Shop at Winrock: An Analysis of a Shopping Center,” New Mexico Architect, May-June 1961, 8-10. ↩

-

Dan Mayfield, “Winrock’s Full-Circle Face-Lift,” Albuquerque Tribune, 19 April 2002, 7. ↩

-

“Victor Gruen’s Malls”, Mall Hall of Fame, accessed 20 October 2015, http://mall-hall-of-fame.blogspot.com/search/label/Victor%20Gruen%27s%20Malls. ↩

-

Mayfield, “Winrock’s Full-Circle Face-Lift,” 10. ↩

-

Benson, “It’s Fun to Shop at Winrock,” 10-12. ↩

-

Abarr, “The Garden That Grew Money,” 18. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

“A Pictorial Guide to Winrock Center,” Folder “Malls & Shopping Centers,” Subfolder “Coronado & Winrock,” General Vertical Files, Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM [hereafter General Vertical Files]. ↩

-

“Celebrating 25 Years,” Folder “Malls & Shopping Centers,” Subfolder “Coronado & Winrock,” General Vertical Files. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Diane Velasco, “Winrock in Limbo,” Albuquerque Journal: Business Outlook, 9 January 2003, 5-6. ↩