1963

Flatow, Moore, Bryan and Fairburn

Case study by:

Stefan Johnson,Fri Oct 09 2015

Travelstead Hall

Flatow and Moore did more than any other firm to break the tradition of dull, oversimplified Territorial architecture that had prevailed in Albuquerque through the late 1940s. George Pearl1

Travelstead Hall, an iconic part of the University of New Mexico’s College of Education complex, is the quintessential example of how Max Flatow’s design language cut through the architectural status quo in New Mexico. Upon opening in 1963, it represented a sharp contrast to the Pueblo Revival-style buildings that predominated on UNM’s campus and throughout Albuquerque. Flatow firm’s design, with its sharp lines, abstracted form, and a bold stained glass wall, was truly innovative at the time, bringing modernism to the heart of the city’s major university. Flatow drew his inspiration from the larger trends of contemporary architecture in the postwar era. Yet, in subtle ways, he did not fully abandon regional historical precedents in determining Travelstead Hall’s form.

The building’s history began when, in 1956, Chester Travelstead, the recently arrived dean of the College of Education, proposed the construction of an all-new facility for his faculty and students. Travelstead disapproved of the dilapidated state of the college’s existing buildings. In 1958 the faculty rose in protest of these conditions, prompting UNM’s present, Tom Popejoy, into action. Popejoy recognized the college’s dilemma and prioritized the project, forming a committee to spearhead it.2 This committee included Professor Alexander Masley, Wilson Ivins, Grace Elser, William Runge, and Charles Travelstead. Donald Schlegel, an architecture faculty member, later the founding dean of the university’s School of Architecture and Planning, and the strongest voice for architectural modernism on campus, was appointed as a consultant to oversee the project.3

In April 1960, Max Flatow wrote Popejoy expressing interest in working with the university, in an effort to obtain the contract for the College of Education project. In the letter, Flatow indicated several reasons why Flatow, Moore, Bryan, and Fairburn, one of the largest postwar architecture firms in Albuquerque, would be the best choice for the job. First, the firm had been practicing near the university for ten years, and had therefore become closely associated with it. Two of the firm’s partners had taught classes at UNM, and all of the partners had previously served as advisors for various university planning committees. Flatow also highlighted his methodology of structural simplicity, order, and efficiency, along with his planning expertise. He suggested that a truly modern building could be achieved here, while still maintaining the look and feel of the Southwest.4

Flatow’s suasion apparently worked. In 1961, Travelstead and Flatow presented a “pre-preliminary” plan for the project to the university’s regents, a proposal they accepted after Flatow promised the plan would follow the “Pueblo Style.” The university approved full preliminary plans in April 1961, granting the architects permission to proceed. Although controversial at the time, the sanction of these plans – and the particular architectural approach that Flatow took to his task – ended up affecting future architectural work at UNM more than any other event since John Gaw Meem’s design work in the 1930s (a fact later commemorated in part by the renaming of Travelstead Hall after its greatest backer, in 2003).5

The Warnecke Plan

Around the same time that the educational complex was getting underway, the university hired John Carl Warnecke and Associates, of San Francisco, to draft a new campus development plan. Warnecke’s General Development Plan, completed in 1960, marked a shift for the university’s planning scheme.6 Warnecke’s plan sought to develop a pedestrian enclave in central campus, closing the through streets that had run through it and creating walkable malls. To achieve this, the plan proposed a ring road with parking located at the periphery, a scheme that later came to fruition. Other main concepts of the plan included siting new buildings to create outdoor or partially enclosed courtyards and patios, locating the medical center on the north side of campus while expanding the sports facilities on its southern side, creating a green area west of the library (which became the Duck Pond), and retaining established density and architectural character on the central campus.7

The Warnecke development plan likewise had a crucial impact on the site selection and organization for the School of Education complex and, as a result, for Travelstead Hall. The new building’s chosen site, northeast of UNM’s center, required the closure of Cornell Avenue though the campus. This was an unpopular move and a relatively unconventional one in an era marked so significantly by the public’s love for the automobile.8 Indeed, much of the development in Albuquerque at this time reflected its orientation to the car, including shopping malls, houses, and office buildings all oriented to its convenience. Thus, the way people interacted with Travelstead Hall and the education complex was unique amidst the majority of the architecture being built elsewhere in the city in the same period. The complex was a key part of the effort to realize UNM’s new spatial typology of walkable, enclosed outdoor areas of various sizes, as described by the Warnecke Plan. Flatow’s project capped the northern end of the new Cornell Mall, enclosing central campus and marking a significant shift from the automobile-oriented streetscape that had dominated previously.

Design Significance

At the time of completion, the design of the complex as a whole created quite a buzz. Flatow preserved the essence of the campus’s Pueblo Revival style while pushing its boundaries, especially by abstracting and incorporating an eclectic mix of Pueblo and regional influences.9 For example, Flatow’s designs for the complex referenced Pueblo ruins, specifically what he called the “Indians’ mastery of using masonry walls and buildings to create outside usable spaces.” He referred to this as the “mesa wall theme.”10 Perhaps the most explicit reference to regional revival styles could be found in the stucco solar shades that appeared on Travelstead Hall’s northern and southern facades, a material that had become synonymous with local interpretations of historic styles.

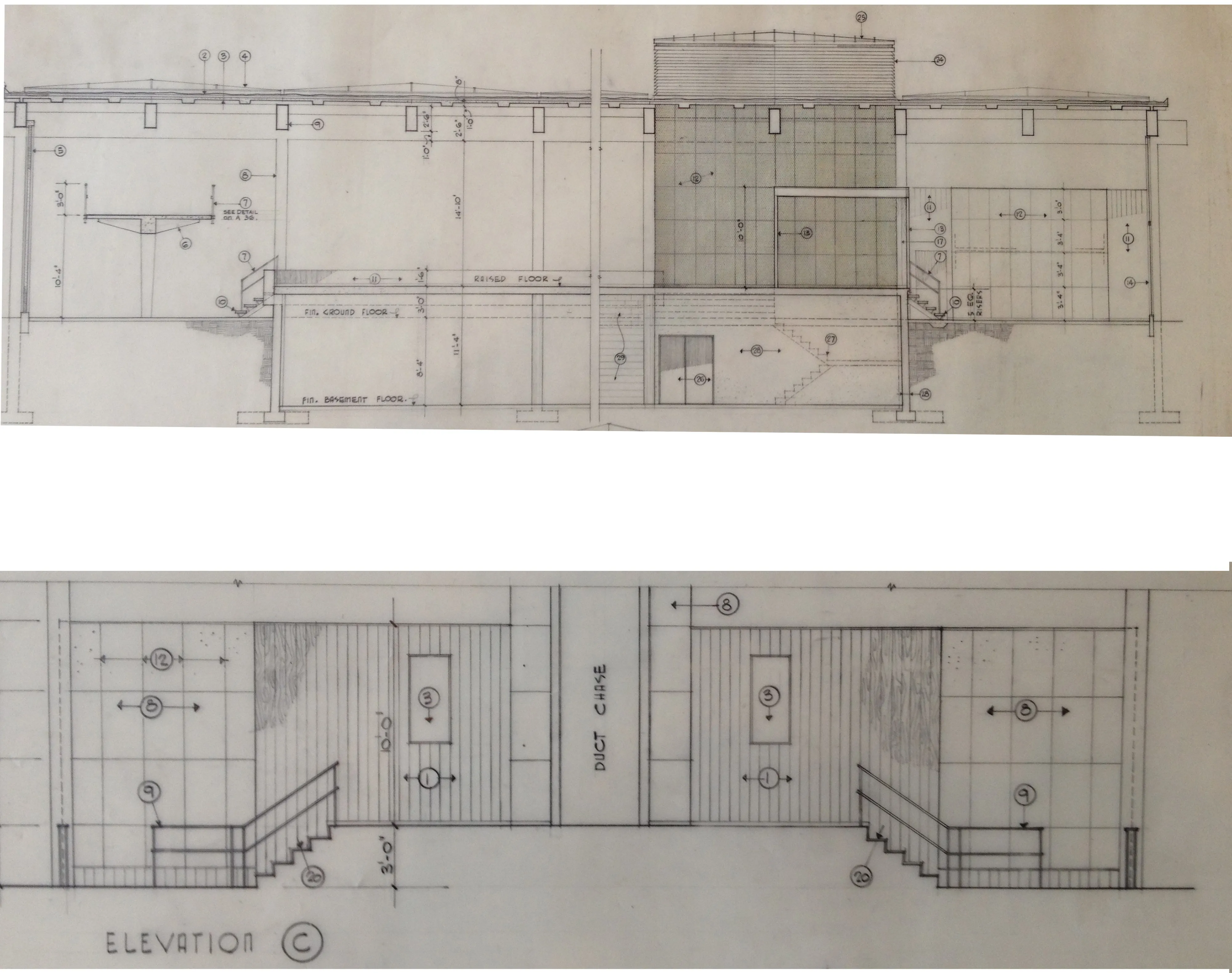

Yet if you were to separate Travelstead Hall from its surrounding context, it would be quite difficult to identify the design cues that Flatow used to root it in New Mexico. In fact, compared to the other buildings within the education complex, Travelstead Hall displayed the least obvious use of such regional influences. Much more evident, even today, is the uncompromising modernism that characterized the work of Flatow’s firm. The beauty of this building comes from its simplicity and the rhythm of architectural elements throughout. Essentially a rectangle in form, Travelstead Hall’s longest sides run along the north and south of the building. Flatow carried this simplicity through to the material palette, which depends extensively on reinforced concrete, itself a key modernist element, creating a duality between function and austere beauty. In contrast with the heaviness of its concrete walls, the north and south facades feature floor-to-ceiling glass curtain walls that zig-zag to avoid obstructing the two main corridors running the full length of the building. These curtain walls wash the interior with ample daylight, a bold statement in line with the architectural zeitgeist of the day. Most dramatically, Travelstead Hall’s western facade consists of a stained glass wall designed by artist John Tatschl.11 This aspect of the building was the defining feature that set it apart from all other buildings on campus, creating a light, glowing elevation inside – during the day – and from the outside in the evening. The roof and ceiling contrast with large concrete beams, columns, and precast T-slabs that recall the materials of the interstate highway system under construction in the same era. But Flatow’s decision to angle the roof slabs at 45 degrees, alternating between beams, creates visual relief from orthogonal beams and columns. This detail allows a row of skylights to run the length of the building, minimizing the roof’s heaviness and bringing yet more light inside.

Travelstead Hall displays the essence of the modernist open floor plan, made possible by the concrete beams spanning its expanse. Its layout within that span consists of a modified cross-axis form. Flatow designed the circulation as an “H” with two long corridors running along the north and south that service the east and west sides of the building and a center corridor running north-south that connects its components and provides access to the rest of campus. The building’s program resides on and underneath a central plinth. Atop that plinth stands its office space. Privacy is achieved here with freestanding prefabricated rooms that terminate before reaching the ceiling, preserving the overall openness of Flatow’s design. These structures housed higher-ranking administration, with all other work areas situated out in the open, defined by low furniture. Below the plinth stands the service program (mechanical and storage), leaving the main floor spacious and uncluttered.

These aspects relate Travelstead Hall to some of its most noteworthy contemporaries in this era. Flatow’s organization of programmatic space recalls Louis Kahn’s distinction between “servant” and “served” spaces. Kahn separated certain programs to emphasize and enhance the sense of order and composition in his works. In Kahn’s Salk Institute, for example, completed in 1965, he dedicated entire floors to mechanical considerations. Similarly, in Travelstead Hall, Flatow implements a similar tactic: everything that the user of the building comes into contact with is free from the mechanics of the building. Even the mechanical ductwork is hidden from view. Similarly, tucked beneath the building’s plinth, mechanical functions are uncluttered by the user-based program. Other elements of Travelstead Hall, especially those relating to the elegance of its design, draw similarities to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s work, such as his Crown Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology, completed in 1956. In particular, Mies’s idea of “universal space,” a conception of the interior as a long, singular volume that could allow flexible subdivision, relates to Flatow’s approach to the interior here, with its large, open volumes. Flatow’s focus on austere, exposed structure and materiality at Travelstead Hall likewise relates to Mies’s approach, as well as that of many other key postwar modernists.12

Yet even as it recalled these and other experiments in American midcentury modernism, Travelstead Hall created a space that very much embodied Flatow’s own approach to creating a warm, elegant modernism evident throughout his Albuquerque projects. More than this, the work of Flatow’s firm here set the precedent for future buildings at UNM to push the envelope with innovative forms and materials, while still nodding to traditional elements of design.13 Travelstead Hall and the broader education complex of which it was a part represented an important shift in the university’s design language, setting the tone for architecture that did more than just satisfy the status quo. With its sharp lines and modern details, Max Flatow’s staunch belief in architectural innovation, on display here, promoted creative freedom for other architects to build from and study.

Footnotes

-

“Inventory of the Flatow, Moore, Bryan & Fairburn Job Files, 1957-1984,” Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico, accessed November 16, 2015, http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmumss801bc.xml#idm212832. ↩

-

Van Dorn Hooker with Melissa Howard and V.B. Price, Only in New Mexico: An Architectural History of the University of New Mexico: The First Century, 1889-1989 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2000), 160-161 ↩

-

Ibid., 161. ↩

-

Letter to Tom Popejoy from Max Flatow, 4 April 1960, Box 3, “Architect – Flatow, Moore, Bryan, and Fairburn 1960s, 76,” University of New Mexico Dept. of Facility Planning Records (UNMA 028), Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM. ↩

-

Only in New Mexico, 161. ↩

-

“UNM Albuquerque – Campus Development Plan,” ca. 1995, accessed November 16, 2015, https://iss.unm.edu/PCD/university-planning/master-planning/archives/Development/UNM_CH01.pdf, 16. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Only in New Mexico, 161. ↩

-

“UNM Heritage Preservation Plan,” accessed November 16, 2015, https://iss.unm.edu/PCD/docs/Getty_Report/GettyProject_Vol1_SecB-HeritageZones.pdf, 128 ↩

-

Only in New Mexico, 161. ↩

-

Ibid., 164. ↩

-

On Crown Hall, see, for example, Adelyn Perez, “AD Classics: IIT Master Plan and Buildings/Mies van der Rohe,” ArchDaily, 16 May 2010, accessed 19 Oct 2015, http://www.archdaily.com/59816/ad-classics-iit-master-plan-and-buildings-mies-van-der-rohe/. ↩

-

“UNM Heritage Preservation Plan.” ↩