1965

Arthur W. Dekker

Case study by:

Samuel Strasser,Sun Oct 09 2011

A.W. Dekker House

Introduction

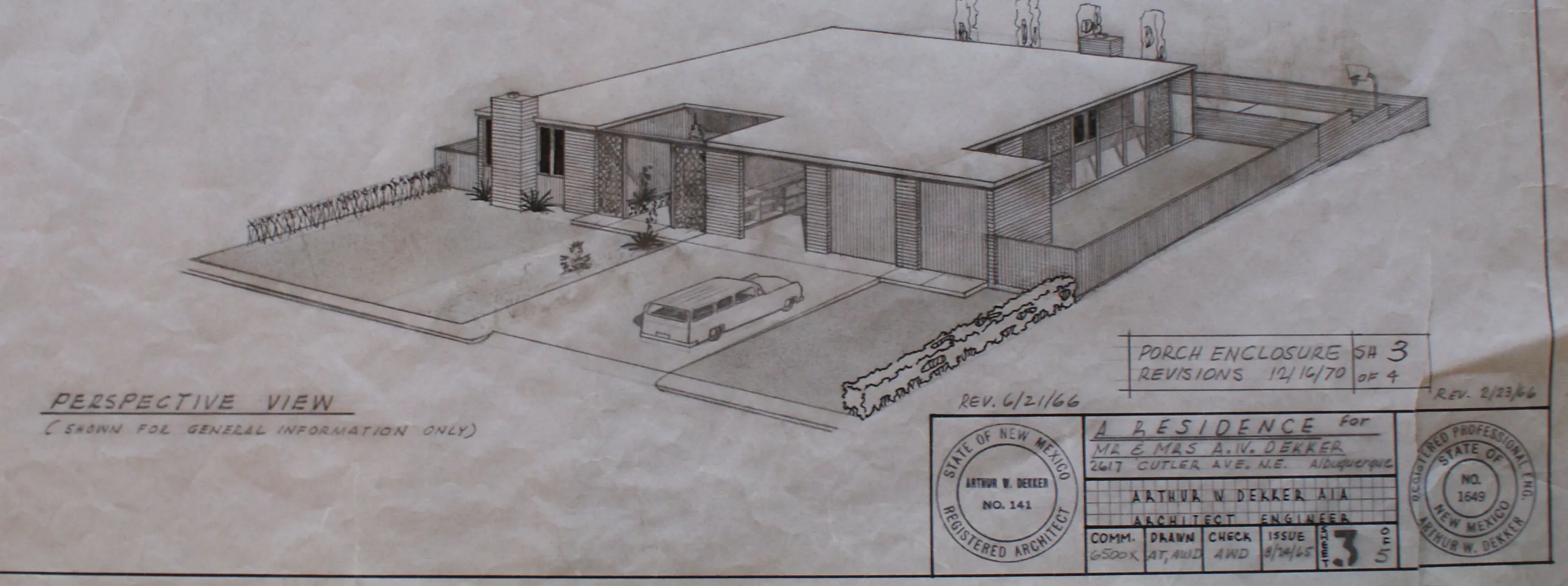

Architect Arthur W. Dekker’s house, built in 1965, is located at 2621 Cutler Ave. NE in Albuquerque, just north of the North Campus of the University of New Mexico and seated at the end of a diversion channel near the interchange of I-25 and I-40. In its day, the Dekker House would have been at the heart of the growing city, for the residence sits on a piece of land where the old Sandia Base laid to the east, Kirtland Air Force Base stood to the southeast, the University of New Mexico rose to the south, and Albuquerque’s downtown stood to the west. The Dekker House’s design is simple and unadorned, primarily consisting of rectangular forms for its design scheme, in both plan and elevation. Then and now, Dekker’s house served as a prime example of modern lifestyles in 1960s Albuquerque. The Dekker House was a symbol to the owner’s neighbors and the greater constituency of Albuquerque of the architect’s prowess as a modern designer. The house not only reflected the architect’s own talent but also his own values and the values of the nation at the time. The Dekker House is a great tool to dissect the history of postwar Albuquerque; contextualizing the modest home reveals it as part of a greater story. However, to understand the house one must first study the architect who designed it, for events that occurred in the architect’s life would influence the house he built for himself and his family in Albuquerque’s booming northeast quadrant.

Arthur Dekker was born on October 3, 1922 and grew up in Roswell, New Mexico. He received a Bachelors of Arts in Architectural Engineering in 1948 from the University of Kansas. During his 50-year-long career as an architect, Dekker designed well over one thousand buildings and other structures mainly in New Mexico.1 The firm he established in 1959, Art Dekker Architects – after breaking away from Brittelle, Ginner and Associates – would later become Dekker/Perich/Sabatini (DPS), one of the largest firms in present day Albuquerque.

Dekker’s early years on his own consisted mainly of renovation projects, churches, and residences. Home construction at this time was a booming market. Dale Bellamah, Sam Hoffman, and Edward Snow attained large sums of wealth and success developing vast plots of empty mesa into neighborhoods for Albuquerque residents. This surge in market demand for homes was mainly due to defense spending during and after World War II in the Albuquerque region. After the U.S. government took over the municipal airport near Gibson Road and turned it into Kirtland Air Force Base and the army established Sandia Base just east of Kirtland, there was a huge surge in the local wartime economy in Albuquerque.2 Defense job opportunities as well as the arid climate drew large amounts of people into the region. Due to this population boom, developer titans Bellamah, Hoffman, and Snow thrived. For example, huge lots of land were subdivided and developed near the main gate of Kirtland Air Force Base on Wyoming Boulevard. These suburbs appealed mainly to working-class individuals who came to Albuquerque seeking new job opportunities. However, large-scale as well as small-scale home developers and designers saw increases in demand. Gaps in the market for higher end homes that Bellamah, Hoffman, and Snow could not fill went to small-scale firms such as Art Dekker Architects.3

Small architecture firms saw their fair share of work in Albuquerque at the time. A surge in wealth in the area allowed for a wide enough gap in the market to sustain small enterprises like Dekker’s. As historian Robert Turner has explained, “Accompanying the headlong growth in business and government during this period – both making the growth possible and also being fed by it – was a leap in personal income on a scale rarely seen.”4 This surge in wealth made it possible for people to own more material objects such as home appliances, homes, and automobiles. Retail sales of automobiles, as a percentage of total national retail sales, rose from 15.6 percent to 20.2 percent between 1948 and 1958, and national home ownership rose from 56.8 percent in 1940 to 68.3 percent in 1960.5 The Albuquerque Journal stated in a 1958 editorial that “as homeownership grows, so is our democracy strengthened.”6 In 1957 the National Association of Real Estate Brokers outlined reasons for owning your own home, some of which were for the “development of responsibility and character.” The author continued, “The homeowner feels greater responsibility towards his dwelling and the neighborhood. Such responsibility makes the homeowner a better citizen by increasing his interest in civic manners.”7 Material wealth seemed to not only define the success or “worth” of an individual but also to shape his or her integrity through an associated engagement with civic interests.

Dekker took an interest in these civic duties. He served in the Air Force in Tinian, Saipan, and Iwo Jima in World War II and again served from 1951 to 1954.8 In January of 1957, having returned to New Mexico, Dekker was nominated as the treasurer of the state chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).9 That same year in May, Dekker allotted cash prizes to four UNM architecture students as part of an AIA awards banquet.10 Dekker was obviously devoted to his community and nation, but as described above by the National Association of Real Estate Brokers, in this era a man’s worth was not only set by his actions but also by his possessions.

Amidst this prevailing social norm, Dekker accrued wealth and continued running his own firm in order to create a symbol of his own success. This symbol would manifest itself in a house for the architect and his family. The area in which Dekker sought to design his house was an established neighborhood called Netherwood Park. Maps of this area dating to 1957 show the prospect of I-25 and I-40 meeting not too far from this neighborhood in what is now the Big “I” interchange.11 In 1965, at the time of the home’s design, maps showed the construction of a diversion ditch following Cutler Avenue right before the completion of the I-25 and I-40 interchange.12 Officials demolished a large portion of the existing neighborhood to make way for the interchange and diversion ditch. This would have led to a good opportunity to grab cheap land near the interstate entrances.

And so Dekker completed his drawings for the house on August 24, 1965 with a stamp from the city approving the commencement of construction on his residence.13 The style of the house was very unique for its time and place. For much of the 20th century, the Southwest as a whole had strived to create an identity of its own in places like Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, and San Diego through the widespread use of the Mission Style, Spanish Revival Style, and Pueblo Revival Style. But Dekker rejected these regionally popular approaches, instead choosing to design a house in the modernist idiom.

Formal Characteristics

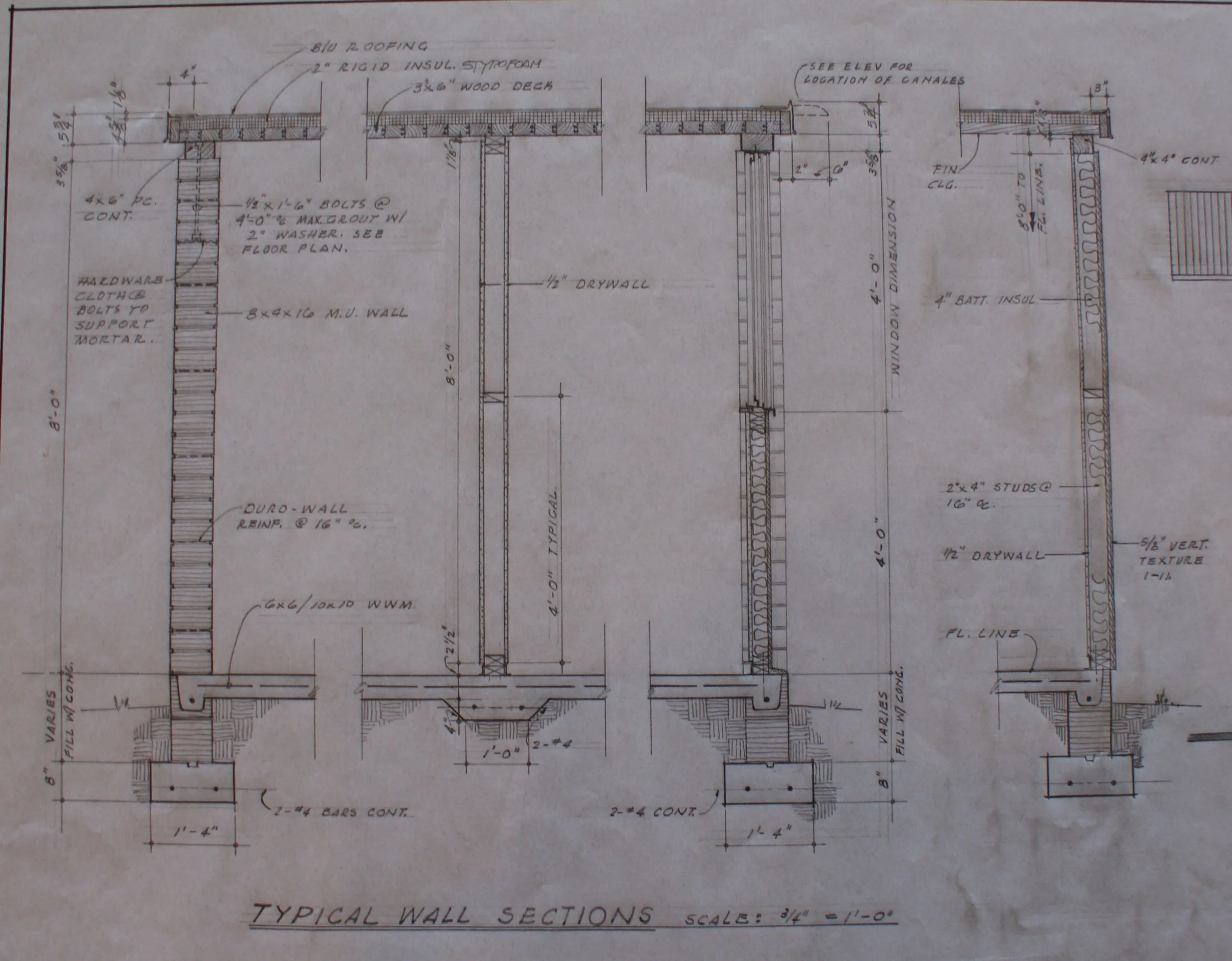

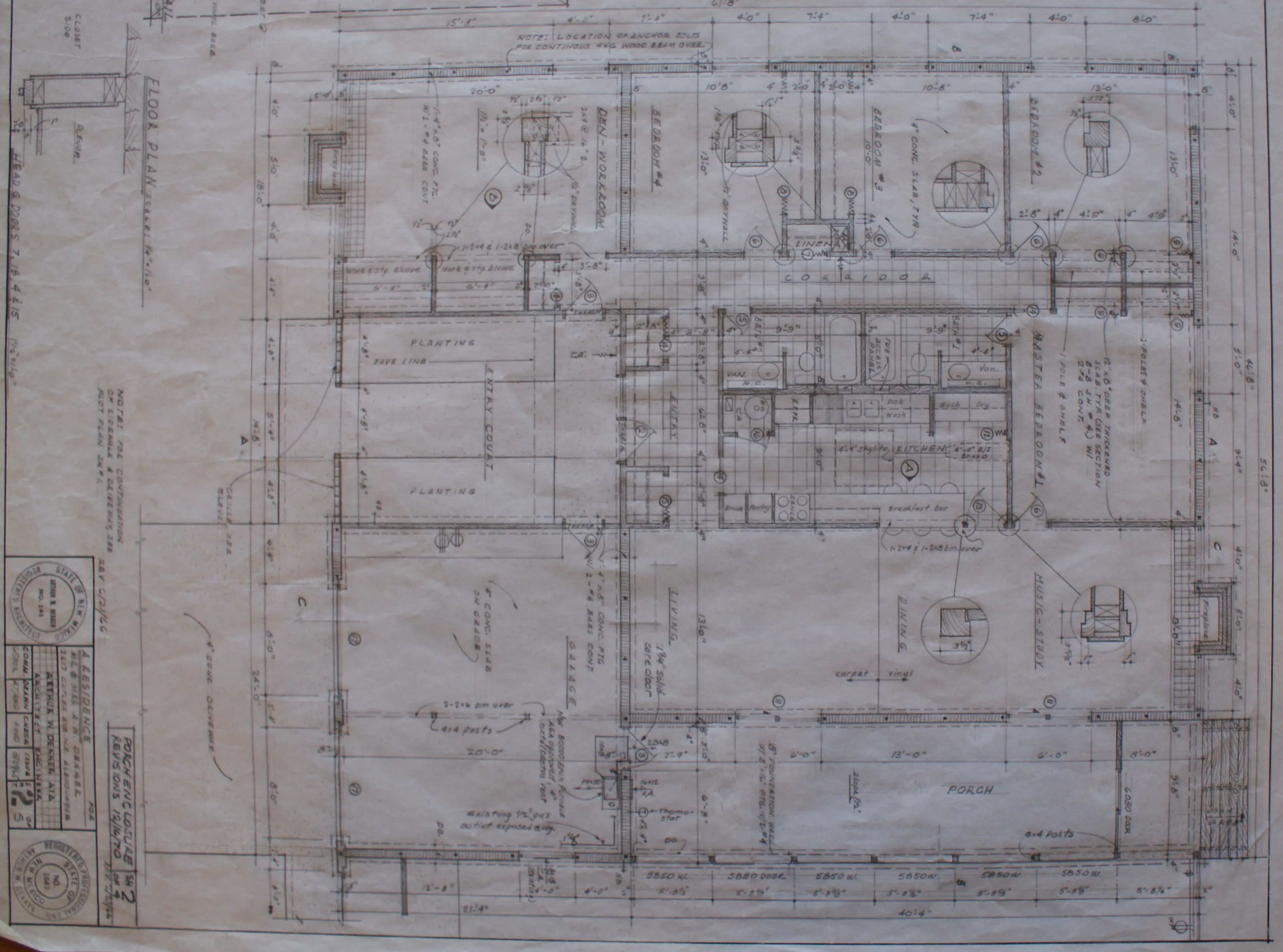

As one can plainly see in both Dekker’s drawings and the completed house itself, many of the elements in the residence are unadorned, as was typical with mid-century modernism. The implementation of unadorned structural masonry walls is one especially interesting aspect of this residence. Though most of the exterior walls are made of masonry, a few of the interior walls are masonry as well. There are several reasons why Dekker likely chose to use masonry in this manner. The first reason for doing so is mainly structural, due to the continuous four-by-six inch wood beams spanning the eighteen feet of width of the west wing of the house, as noted in the floor plan of the residence.14 Given Dekker’s training as both an engineer and architect, this seems to be the most obvious reasoning. However, the use of masonry here was nevertheless an unconventional gesture since masonry would have still been the more expensive option when compared to structural timber. Secondly, concrete masonry units (CMUs) were the cheaper alternative to cast-in-place concrete yet still enabled Dekker’s material experimentation. Concrete was seen as the material of the future and certainly one of the materials of choice for modernist designers, but it was generally considered best suited for commercial projects. Dekker’s use of a concrete wall in a residential building here was more than a practical choice, then, but also one that made a strong and dramatic architectural statement about residential design in a new era. CMUs would have provided a good compromise between cost and Dekker’s intent and could help explain the intention behind his chosen materiality here.

The Dekker Residence also has an open floor plan, which is common with modern homes of this time. When one enters the residence there is a hallway leading either to the left or right. To the left is the west wing where one finds the more private, family-oriented areas of the house. Three children’s bedrooms run alongside a hallway that extends the length of the house. As the end of this hallway, one finds the den. To the right of the entrance, in the east wing of the house, one finds the more public area of the house. The music room, dining room, and living room occupy an unimpeded space of 13 feet by 40 feet here, which would have been considered a vast open space prior to the emergence of modernism. In between these wings, in the center of the house, stand the kitchen and master bedroom. The master bedroom has access to both wings of the house, which would have been a beneficial feature for someone who enjoyed entertaining guests while keeping watch over their children. The kitchen holds all the modern features a housewife would have needed to complete her daily chores in that era. A dishwasher, refrigerator, stovetop, clothes washer, dryer and foldout ironing board all occupied this space for the benefit of the chic housewife.

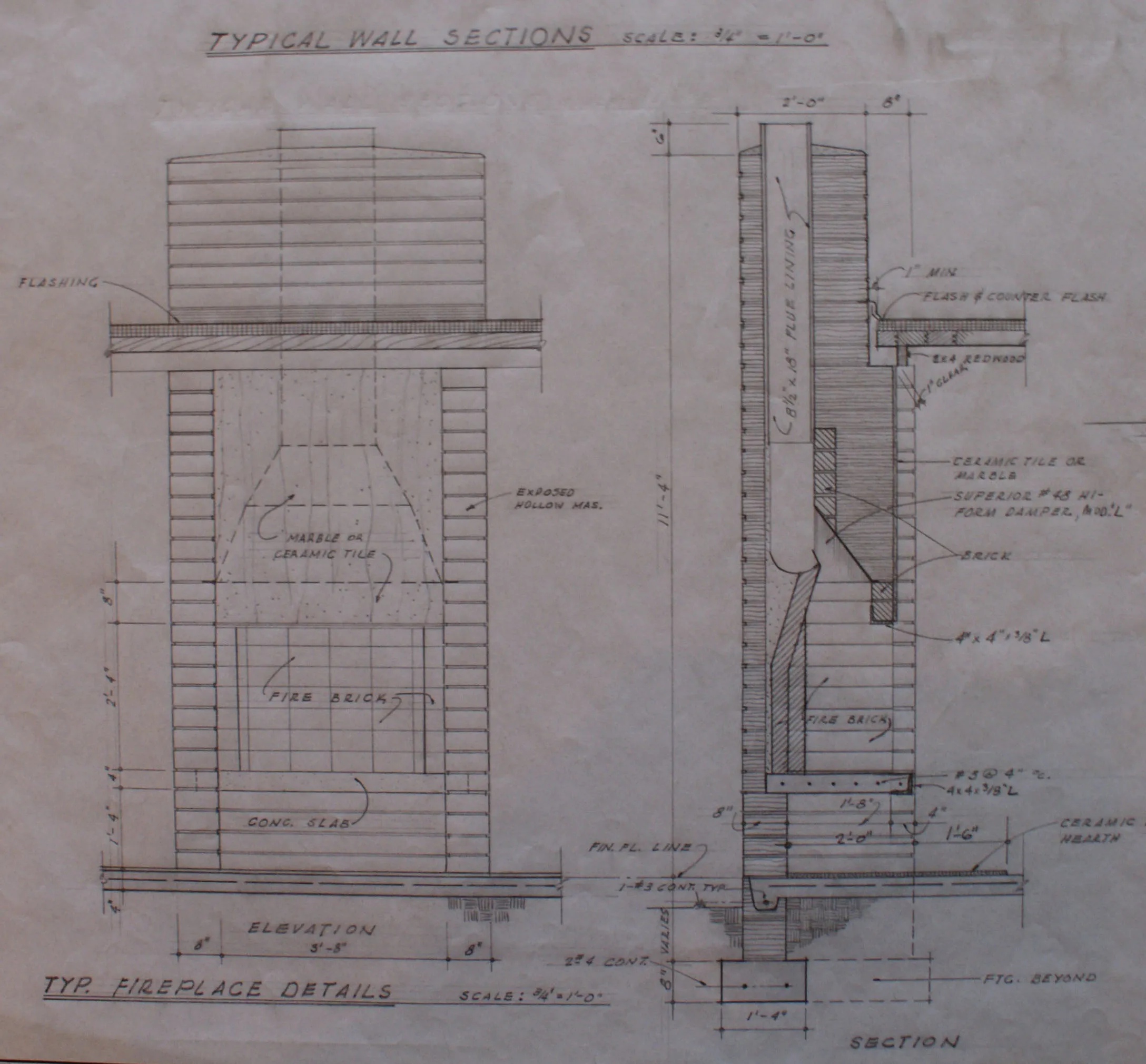

The Dekker House not only showcased Dekker’s modernist sensibilities, it also showcased his modernist lifestyle. The residence could house two automobiles, which was quite extravagant at the time even for the automobile-loving citizen. Moreover, Dekker designed a utility shed to look like a third garage to further this perception. Two fireplaces are key elements in the family/common areas, one of which is located in the front den, facing the street. This gesture showcased the occupant’s family orientation to visitors and neighbors approaching the house. The fireplace was also a gesture of wealth and class, a fact revealed even today in its rich materiality. Redwood trim adorns the wall where the fireplace brick meets the roofline and marble adorns the space above the firebox as part of the overmantle. Though not a symbol of excessive affluence, the thoughtful and elegant manner in which Dekker assembled the details of this residence would have conveyed a finer design aesthetic and higher level of ability to prospective clients than the houses constructed by Bellamah or other competitors.

One example that clearly illustrates Dekker’s attempt to create a thoroughly modernist work here is the detailing of the roof, or rather the suppression of the roof as a detail. The restrained roofline here can be seen in other modern residential architecture, such as that of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Mies’s Lemke House, built in 1933 in Berlin, shares several qualities with the Dekker House. Both residences consist of simple geometries and box-like appearances. Simple, unadorned materials, and the suppression of the roof as a detail are consistent design strategies for both homes. This approach to designing the roof is not only a simplification of the roof element itself, but also contributes to the overall box-like aesthetic of the houses. The result is a minimalist composition, one that was equally dramatic in prewar Germany or in the booming postwar suburbs of Albuquerque, where the house stood out – and continues to stand out – among its neighbors.

The Dekker House was not only a symbol to prospective clients of Arthur Dekker’s prowess as a designer, but also speaks revealingly about the happenings of the time. Its unadorned style connects it to the larger movement of architectural modernism. The front of the house conveys a sense of wealth and family due to the positioning of the two-car garage and fireplace, respectively. Dekker obviously designed this house to make a statement, and that statement not only tells us about Dekker as a person but also speaks to later generations about the history of 1960s Albuquerque and the city’s rapid movement into a new architectural and social era.

Footnotes

-

“Inventory of the Arthur Dekker Drawings Collection, 1959-1970,” Center for Southwest Research, University of New Mexico, accessed November 12, 2015, http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuswadekkerdrawings.xml. ↩

-

Robert Turner Wood, The Postwar Transformation of Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1945-1972 (Santa Fe: Sunstone Press, 2014), 67. ↩

-

Ibid., 113. ↩

-

Ibid., 116. ↩

-

Ibid., 117. ↩

-

Ibid., 117. ↩

-

Ibid., 118. ↩

-

“In the Service,” Albuquerque Journal, 17 April 1953, 39. ↩

-

“Architects Vote to Oppose State Limits on Fees,” Albuquerque Journal, 20 January 1957, 2. ↩

-

“U Architecture Students Receive $600 in Prizes,” Albuquerque Journal, May 9, 1957, 17. ↩

-

Albuquerque National Bank, “Map and Street Guide to Albuquerque, New Mexico,” 1957, Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC), University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM. ↩

-

Western Map Company, “Street Map of Greater Albuquerque,” 1965, MAGIC, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM. ↩

-

A.W. Dekker, “A Residence for Mr. and Mrs. A. W. Dekker,” 1965, Stack 31, Drawer 10, Folder 1, Arthur Dekker Drawings Collection (SWA Dekker Drawings), Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM [hereafter Dekker Drawings Collection]. ↩

-

A.W. Dekker, Floor Plan, “A Residence for Mr. and Mrs. A. W. Dekker,” 1965, Stack 31, Drawer 10, Folder 1, Dekker Drawings Collection. ↩